Life Insurance for Seniors in Canada

Is permanent life insurance a good investment for Canadian retirees?

Is whole life insurance the secret to building “infinite banking wealth” as I keep seeing on Facebook?

What does term-to-100 mean anyway?

Why is everyone trying to sell life insurance to older Canadians anyway??!!

As hundreds of students have taken my course on how to DIY your personal Canadian retirement plan, I’ve gotten a ton of questions on “investing in life insurance.” I use quote marks there because life insurance is NOT an investment. The investment company might take your money and make investments with it – but we should be clear right off the bat that every Facebook ad that you see talking about “infinite banking” and “investing in life insurance” is trying to mislead you.

Long story short when it comes to life insurance for seniors in Canada: There is a 99.9% chance you don’t need it and can just ignore all the sales talk and confusing insurance terminology. You don’t need “enough to cover a funeral”, you don’t need “to think about insurance as an investment” – you don’t need it at all – unless you check all three of the following boxes:

- Have maxed out your TFSA and RRSP

- Want the forced discipline of having to make investable insurance premium payments

- Want to leave a large tax-free inheritance as part of your estate

Then maybe you can start asking: What kind of life insurance is best for seniors?

I still don’t recommend it even in that situation, but it becomes at least debatable once you reach that level of affluence. Since we’re comparing taxable DIY investing vs life insurance policies we’ll need to dive into some tax math (which we’ll get to later in this article), but always keep in mind that there is great value in simplicity as well!

One key consideration to make upfront is that the majority of permanent life insurance policies are cancelled at some point. This is due to the insuree failing to pay their premiums – and the policy then “lapsing”. Online tech startup PolicyMe states that 88% of universal life insurance policies never pay out death benefits due to people allowing their policy to collapse.

Canada’s Rational Reminder Podcast produced by CFPs Ben Felix and Cameron Passmore stated that in American studies done in 2019, in regards to whole life permanent insurance policies, only 31% of the policies remained in force after 30 years.

What this means is that the average Canadian that takes out a whole life policy fails to pay the premium at some point (forgetfulness, budget concerns, etc.) and at that time, the insurance contract is effectively cancelled, with the insurance company keeping the premiums. Basically, the vast majority of people who pay for permanent life insurance don’t get to realize the benefit of it… or at least their beneficiaries don’t get the benefit.

One other point we should address right up front in the life insurance discussion is that there are massive commissions on the line for people who sell permanent life insurance policies. This does not mean that every insurance salesperson will recommend awful insurance policies, but as with all things in life, everyone should be aware of the incentives involved.

On that same podcast episode as discussed above, Felix and Passmore explain what they learned from their time selling life insurance policies themselves:

“The commissions on insurance policies are enormous [..] when I give the example of a 40-year-old buying a policy for $8,240 per year, the commision on that policy would be at least the first-year premium […] It’s big money.”

“That’s not transparent either.”

Finally, there are niche situations where it might make sense to consider buying a policy if you have a corporation (perhaps you have saved a bunch of money in a holding company), but even in this unique situation, I’d argue there are better options (such as investing in swap-based ETFs within your corporate account). Don’t worry if this paragraph was confusing, it probably won’t affect you, but I’m just trying to be fair to all sides here. We’ll also address this specific scenario further down in this article.

Are You Saving Enough for Retirement?

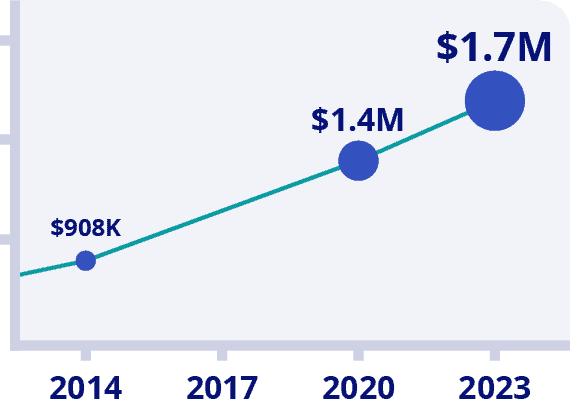

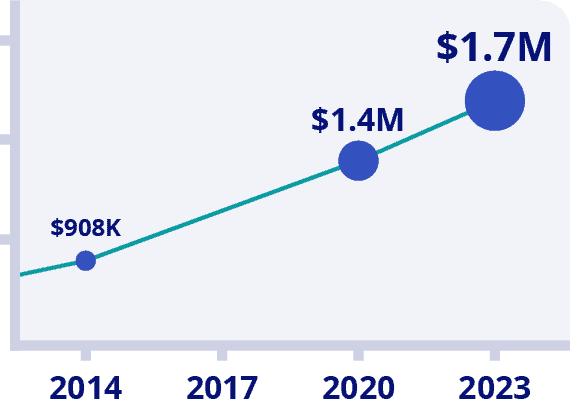

Canadians Believe They Need a $1.7 Million Nest Egg to Retire

Is Your Retirement On Track?

Become your own financial planner with the first ever online retirement course created exclusively for Canadians.

Try Now With 100% Money Back Guarantee*Data Source: BMO Retirement Survey

What Is Life Insurance?

A quick reminder on the basic idea of life insurance: Life insurance allows you to financially protect people who financially depend on you.

There are many different kinds of life insurance, but at its core, life insurance is about replacing the income you would have earned, so that your loved ones will not have to drastically change their standard of living if you were to pass away.

This is clearly an excellent idea. If you have a young family, and have many years ahead of child-rearing costs, mortgage payments, and post-secondary education help to provide, then you need to look into life insurance.

The basic mechanics of most life insurance plans are:

1) You pay a monthly premium to the insurance company.

2) The insurance company takes your money and puts it in a big pool of money from people just like you. The company then pays some really smart math wizards to determine how long the average person contributing money to the pool will live.

3) The insurance company then invests your money in a variety of investments (and according to some pretty solid regulatory rules), and promises to pay your beneficiaries (usually your loved ones, but it can be whoever you name) a specific amount of money (tax-free) if you were to pass away before a certain date.

4) If everything works out and the math wizards were correct, the beneficiaries of everyone who passed away before the specified date will get sent a cheque. The insurance company’s investments make enough money that the insurance company gets to pay all of their employees, pay for advertising, pay for offices, etc – and still send a healthy dividend cheque to shareholders.

If we just pause there for a second, many of you might be thinking: Ok, right, so that makes sense if I have people depending on me.

But one might ask: if I’m retired and don’t have anyone depending on my income any longer, then why would I need life insurance – a product used to protect people in the event that I can no longer financially provide for loved ones?

Well… then you’d pretty much be on the right track. Don’t stray too far from this good common sense!

If you find yourself checking all of the boxes above – then you can find further details about life insurance for Canadian seniors below – but I want to reiterate that this should be one of your last priorities in terms of retirement planning. There are far more important details to take care of before we get to niche topics like this.

What Are the Different Types of Life Insurance in Canada?

There are two main categories of life insurance in Canada: term life insurance and permanent life insurance.

Term life insurance is generally pretty simple and easy to compare between companies. The idea is that you have a basic life insurance contract where in return for your premium each month, you are covered for a specific amount of money for a specific number of years. There is no need to worry about “cash value” or “living benefits”.

If you – thankfully – outlive the policy, then you count yourself blessed, and the insurance company keeps the money you paid, while sending some of it to people who didn’t have your good fortune and passed away while they were insured.

Permanent insurance is where things get a lot more complicated – and it’s the category of insurance most commonly recommended to seniors in Canada for a variety of reasons. It also – almost always – pays a much higher sales commission to the people who sell it.

One of my favourite explainers of all things Canadian finance – Preet Banerjee – does a great job explaining term vs permanent insurance here.

So, under the big “permanent insurance umbrella” we have term-to-100 life insurance, whole life insurance, and universal life insurance. Each insurance company will put their own unique spin on some of these policies, and the specifics can get quite complicated, but here’s the gist of it.

Term-to-100 Life Insurance

The most simple kind of permanent life insurance, term-to-100 life insurance is sometimes referred to as T100. The idea is that you want to pay a straightforward one-price premium for your entire life. Because these types of policies typically have no “bells and whistles”, they are the cheapest type of permanent life insurance.

No worries about managing investments within the policy or “surrender value” or anything like that. Just a simple one-price insurance that you’ll pay until you hit 100 years of age. If you live past 100, the premiums stop, but the coverage continues.

Of course if you decide to quit paying the premiums on this insurance for any reason, the insurance company keeps the premiums you paid, and the contract is ended without any further benefit.

Universal Life Insurance

Universal life insurance is a type of permanent life insurance that is meant to insure you for your entire life. The “universal” part of the name comes from the idea that your policy will allow you to adapt variables such as the death benefit and premiums throughout the lifetime of your insurance contract.

Almost always, there is an element of “paying more upfront – so that you don’t have to pay much later on” when it comes to universal life insurance. Once you pay your premiums, most of these plans give you some element of control over the investments within the policy that you can put your premiums into.

As your investments make money (hopefully) most UL plans give you some sort of option to use that money to buy more insurance, lower your premiums, or as a type of payable cash dividend.

You don’t have to pay extra to buy investments within a universal life policy. You can just pay the life insurance premiums. But one of the reasons to buy a universal life policy is to be able to buy investments, generally structured as mutual funds, that grow tax deferred within the policy.

Whole Life Insurance

Like universal life insurance, whole life insurance is meant to insure you until you go to the great tax haven in the sky. There are two basic types of whole life insurance. “Participating” – or “par” – whole life insurance allows the insuree to “participate” in the profits of the plan – usually by getting a dividend each year (depending on investment performance within the plan).

Non-participating (non-par) whole life insurance is similar, but you generally don’t get paid a varying dividend (because you don’t “participate” in the plan).

Whole life insurance generally offers a contract where you pay a higher premium in your first 20 or 30 years, and then a big part of that money is used to fund investments. The income produced by these investments will then generally pay the premiums for the rest of your life – or a similar setup will be in place depending on the details of the specific plan.

Whole life insurance differs from universal life insurance in that you cannot control what investments your money is put into within your insurance account. The life insurance company will choose the investments on your behalf. The investments are generally a mix of stocks, bonds, and real estate.

For high net worth investors, what is sometimes recommended is a participating whole life insurance plan where the dividend money that you would be getting is automatically used to purchase more insurance. In that situation, you are essentially using your investment gains, to purchase more insurance – and not getting taxed on those gains along the way.

The Hidden Tax On Canadian Life Insurance

At the end of the day, the fees on these life insurance products are much higher than the fees you’d pay if you took your premiums and just invested your money in a non-registered investment account. Head of Research at PWL, Ben Felix (who is also a CFA and CFP) stated on his Rational Reminder podcast that in his research, “Typically, the fees are well above 2%”.

Let’s say that “well above 2%” means 2.5% for the purposes of actually trying to paint a big picture of what this all means.

That 2.5% in fees is going to get charged on ALL of the investments that get made within the universal or whole life policies. It will get charged rain or shine, whether the investments have good years or bad years.

If you invest money on your own, and the stock market has a bad year, you don’t pay taxes on the gains in your portfolio – in fact, if you use tax loss harvesting, your portfolio’s bad year can generate tax deductions to offset other taxes that you might owe on previous or future capital gains.

Now, 2.5% doesn’t sound like much. But remember, this is 2.5% of the entire investment NOT the amount of money that the investment made that year!

So, given that many insurance companies are conservative in their asset allocation, and many Canadian retirees don’t want to embrace a volatile mix of investments, let’s be generous and use a 6% investment return in our calculations.

Given the track record of active money management in Canada, and that most retirees will probably choose to have a generous helping of fixed income like bonds in their investment mix, I think 6% is probably a touch high, but let’s give the benefit of the doubt.

That 2.5% represents a 41.6% “tax” on your average investment year. The only difference is that in this case the tax gets paid to the insurance company instead of to the government. That “tax” in the form of fees paid to the investment company could be money staying in your hands if you simply invested that premium payment money on your own.

But Canadian Life Insurance Plans Offer Tax-Free Growth Right?

The argument in favour of using life insurance as an investment revolves around the premise of a magical tax-free pot of gold at the end of life’s rainbow. Canadians generally LOVE the idea of getting out of paying taxes. It’s an idea that is easy to understand, and easy to explain at a surface level. When it comes to paying life insurance premiums in return for a payout upon death however, we have to ask ourselves how much tax we would actually be paying if we just invested the money on our own instead of handing it to a life insurance company.

Investment income and gains made within whole life and universal life insurance plans are tax-free in most situations.

BUT – the question becomes, is that tax-free benefit worth paying for the fees and probable underperformance of the investments within the plan compared to cheaper investment options?

Not to mention the fact that you have to sort through all the paperwork and complexity of the plan as well.

Let’s look at the average rate of tax a Canadian is going to pay on their investments if they just took their money and invested it in a non-registered account. (I’m not going to bother comparing to an RRSP or TFSA, because as I explained at the top, that comparison isn’t even close. If you still have room in your RRSP and TFSA, then you shouldn’t be worrying about complicated insurance products at all.)

Given the amount of tax credits and income splitting options available to seniors in Canada, it’s quite likely many middle-class Canadian retiree couples will pay a lower tax in retirement than they did while they were working.

Income from sources such as part-time work, CPP, OAS, private pensions, and RRSPs/RRIFs will be taxed the same way as income you would have earned at a job before retirement. As an example, let’s say for an above-average income retiree couple, those sources of income could add up to $30,000 each in retirement.

TFSA withdrawals are obviously tax-free under any circumstances, so no need to worry about paying taxes on that income, or having that money “push you into a higher tax bracket.”

If we look at our hypothetical couple from above, they will each have about $23,000 of “earnings space” available to them before they hit the second federal income tax bracket. Now, the provinces are also going to take their tax bite. Ontario’s first tax bracket goes up to almost $50,000, BC’s goes up to almost $46,000, Alberta’s goes up to $142,000, Quebec’s about $49,000. So as a ballpark, we’ll say that our “above-average” retiree couple with maxed out TFSA and RRSP accounts has about $20,000 in earnings space, before they hit that next tax bracket.

In most cases, the relevant tax rates that we want to look at when trying to decide if we need permanent life insurance are those in that first tax bracket. Here’s the roughly combined federal/provincial tax rate that you’d be looking at depending on what investments you’d have in your non-registered portfolio and what province you’re in.

- GIC/Bonds/High Interest Savings: 20-25%

- Capital Gains: 10-14%

- Canadian Dividends (once the dividend tax credit formula is applied): 0%-5%

Quick Note: We’ll leave corporate taxation aside for a second – just know that the dividends I’m referring to here are the dividends we’d get from investing in stocks in our online brokerage (called eligible dividends) – and that dividends from private companies are usually non-eligible dividends and have their own tax treatment.

You can see again why we put so much emphasis on putting the right investments in the right spots when we discussed Withdrawing from your TFSA, RRSP, and Non-Registered accounts.

Now, I don’t know too many Canadian retiree couples who want to pull out more than $40,000 per year ($20,000 each) from their combined non-registered investment account. If that $40,000 consisted of mostly Canadian stocks, you’d be looking at withdrawing all of the dividend money each year, and probably selling off some of the stocks each year too.

Part of that money from selling the stock is going to be tax-free (the original money that you paid for the stocks is just your own after-tax dollars coming back to you) and then part of the money (the gain you made) is going to be taxed as a capital gain.

While you should be able to shelter the bulk of your non-Canadian investments and GICs/bonds in your TFSA and RRSP until later in retirement, it is possible that you would have some of these types of investments in your non-registered investment account as well.

Various tax-saving strategies such as tax-loss harvesting can sometimes be applied to further reduce your tax rates.

So, to get back to our hypothetical couple… If their entire combined income for a year in retirement looked like the following:

CPP + OAS + part-time work + RRSP withdrawals + TFSA withdrawals = $60,000

Canadian dividends (eligible) from non-registered account = $15,000

Non-Canadian dividends from non-registered account = $5,000

Capital gains from non-registered account = $10,000

Your own after-tax money back from selling stocks in a non-registered account = $10,000

Then in this situation our hypothetical couple is going to pay about 9% in tax on the combined investment gains they made when they withdraw their spending money from their non-registered investing account each year. They would also of course withdraw $10,000 that they got back from selling stocks that would be non-taxable.

That’s an example amount of tax that could be saved by putting those investments within a permanent life insurance plan.

BUT – in return for that fairly meagre tax savings, your permanent life insurance plan is going to charge you somewhere around 30-50% of your investment returns in fees (as discussed above).

I don’t know about you, but that doesn’t sound like a great deal to me.

To further complicate matters, when we’re talking about participating whole life insurance, the actual underlying asset that you’re investing into is the profitability of the plan itself, as opposed to any stocks, bonds, or GICs. So your actual dividend is NOT based solely on how the investments do, but instead also includes the actual assumptions that go into determining the overall profitability of the block of plans that you’re a part of.

If you’re thinking this is all way too complicated, you’re almost certainly correct. Ben Felix and Cameron Passmore do the best job possible explaining how this all fits together in this episode of their Rational Reminder Podcast.

Here’s what the team at PWL wrote about participating whole life insurance in Canada:

Participating Whole Life (PAR) insurance shares many of the same features as non-participating WL insurance, with the addition that policyholders can partake in the performance of a collective group of policies. This collective group is known as the block of participating policies.

Effectively, policyholders of participating WL pay a higher premium than the equivalent non-participating WL in order to partake in the performance of the insurance company’s profits, as it relates to all of the PAR policies issued and outstanding.

An insurer will price their products based on assumptions about the future, where the premium is set to reflect expectations of various factors including mortality, expenses, policy lapses and cancellations, policy loans, death benefit claims, and taxes.

Premiums received in excess of claims and expenses are invested in a participating fund, and the insurer then sets additional expectations for the performance of these investments. If the actual experience of the block of PAR policies is better than expected, “dividends” are paid to policyholders in that participating block. Said differently, if the investment performance of the participating account is better than expected, there is a positive impact on participating policyholders.

This is important: many insurance companies will showcase the asset allocation and historical performance of the participating investment fund, but these details are irrelevant to the performance of PAR policies. What matters to participating policyholders is how well the insurance company predicts the performance of the participating fund when they price the premiums for PAR policies.

If taxes and expenses are higher than expected, or if death claims and policy lapses are higher than expected, dividends are negatively affected; policy lapses leave the insurance company with less time to absorb high underwriting costs, sales costs, and commissions.

To represent the expected performance of future policy dividends, marketing materials of permanent policies often illustrate the “current dividend scale” as a percentage. This scale cannot be used to compare insurance providers. The policyholder experience is entirely controlled by the spread between the real outcome and the actuarial assumptions used. The assumptions are kept confidential by insurance companies while the real outcome cannot be reliably predicted with any degree of certainty…

A Canada Life policy illustrated in 2010 at the then-current scale of 7.36% may have left policyholders who purchased on the basis of “current dividend scale” disappointed by the average dividend scale interest rate of 6.23% since then, or the average of 5.75% for the five years ending 2021. This highlights the risk of participating dividends: they are not guaranteed. Insurance companies are upfront about this fact.

All that to say: Look, the returns on participating whole life insurance are ridiculously complex. They are also misrepresented in order to sell a very high-commission product.

What About Permanent Insurance Within My CCPC?

As an intense sceptic about the concept of “infinite banking” and the sales of high-commission permanent life insurance plans, I believe in keeping life simple and ignoring them completely.

That said, if there is one situation where the tax-effectiveness of life insurance really shines it’s when a policy is held within a Canadian Controlled Private Corporation (CCPC). Here’s the quick advantages in this unique situation:

- Your large premium payments each month are tax deductible as they are written off as a business expense.

- The death benefit can be paid out tax free using the Capital Dividend Account within a CCPC.

- Participating whole life insurance dividends can continually be used to buy more units of life insurance, and thus, investment gains are essentially untouched.

Now, it should be pointed out yet again, that all it takes for these policies to completely fall apart is one missed payment. If your corporation ever goes through a rough time – or you need to pull more money out of your corporation than you initially thought – and you can’t pay the insurance premium… wave goodbye to that “cadillac insurance plan” you were depending on a key part of your estate.

Changes to government taxation are another factor to consider. As these types of insurance loopholes are more commonly exploited, they will become more ripe targets for the CRA to go after. Indeed, in a recent interview I did with fee-only advisor Jason Heath (CFP) at the Canadian Financial Summit, he speculated such changes could be coming down the pipeline.

Is There a Time When Buying Life Insurance as a Senior Makes Sense?

It’s debatable.

If you knew ahead of time when you were going to die – and that “your time” was going to come sooner rather than later – then it would make sense to buy life insurance as a senior.

Obviously that’s a pretty tough data point to come up with.

And if your health is poor, and you buy a new life insurance policy, the insurer will tag you as high risk in their underwriting and your premiums will be higher.

I’m also biased towards just keeping things as simple as possible when it comes to handling finances in retirement. Investing the money that would have been used to purchase insurance premiums will give you a lot more direct control, and it’s just so much easier/less complex than worrying about the details of a permanent life insurance plan.

Sure, you’ll pay some taxes when you earn and spend your own money, or when it passes to your estate. BUT, in return you’ll get easy access to your money throughout your entire life, you’ll get to choose the investments, you’ll get to cut fees to the bone, and you’ll get the value of simplicity.

Oh – and you don’t have to worry about the small possibility that the insurance company might go bankrupt at some point in the next 50 years. Admittedly there isn’t a big chance of this occurring, but Google “AIG 2008” if you want to scare yourself a little bit.

There have been three cases of Canadian life insurance companies going bankrupt since 1990. The good news is that due to government regulation, 85% of your policy benefits will be guaranteed in a bankruptcy scenario.

Barring clairvoyant knowledge of your own demise, I think that there is a logical case to be made to look into purchasing life insurance in retirement if you fall into the following situation:

1) You have maxed out your RRSP and TFSA.

2) You have a relatively large non-registered account or a large amount of investments inside a corporate account (probably in the $1 million+ range).

3) You want to pass on the maximum amount of after-tax income to your estate – and that is more important to you than spending on yourself in your golden years.

4) You’d rather pay a high monthly premium than worry about putting the equivalent amount of money in a non-registered account each month.

In this situation, buying some type of permanent life insurance that uses the accumulated investment returns to buy more insurance coverage – is probably a decently tax-efficient way to leave money to your loved ones.

In this situation, the returns on your investment gains never truly get taxed, and the constantly increasing insurance coverage that you buy could come in handy when settling up your estate. Often there are taxes owing on a person’s estate when they own multiple properties, or have corporate tax liabilities.

A life insurance cheque can be used to quickly pay those taxes and simplify things. Life insurance payouts generally don’t have to pass through probate if paid to a direct beneficiary instead of your estate, and so the beneficiaries can get the money quicker.

I would point out that a large amount of money in an investment account can also be used to pay taxes. Large amounts of money can also be gifted to loved ones or donated to charities while still living, so those are other options worth comparing high life insurance premiums to.

In my opinion, one could safely ignore the cash value and all that other stuff, because if you have to worry about borrowing against the cash value, you probably don’t have the net worth and liquidity to be worrying about permanent life insurance in your golden years.

What If I Already Have a Universal or Whole Life Policy?

If you’re reading this and you’ve been paying into a universal or whole life policy for a decade or two already, then you’re almost assuredly best to stick with it if at all possible.

Unfortunately, there are many Canadians each year who are going to decide they no longer need their permanent insurance policy and decide to quit paying premiums, and take the cash surrender value of the plan. This is the worst-case scenario that I identified at the start of this article.

Well… actually, I guess the worst-case is probably that your life insurance gets paid out very early after you start paying premiums. Mathematically, your estate will benefit from this, but uh… let’s just say collecting a life insurance payout has a high cost involved.

So the second worst case scenario is one detailed in this Star article by David Aston. In this type of situation, the need for budget room as one gets older makes the permanent life insurance premium an unaffordable luxury. When the decision is made to collapse the policy, almost all of the value of the monthly premiums paid over the years evaporates. Sure, you might collect a relatively small cash surrender value, but that’s almost nothing compared to if you had just invested the money on your own.

The article above shows how a “well off” Canadian couple was promised 10% investment returns within their investment plan. Of course the investments didn’t even come close to that promised amount, and that left the couple still paying hefty premiums in retirement.

If they fail to pay these massive premiums, they’ll lose the value of all the premiums they’ve paid in the past. Consequently, they have had to cut back on their lifestyle and forego retirement travel plans amongst other luxuries.

So, it does make mathematical sense to keep paying the premiums if at all possible. Maybe ask the beneficiaries to chip in a bit to help if needed? Letting the policy collapse is usually a large net loss to your estate for relatively small gain right now. This is why it’s so noteworthy that so many expensive permanent insurance policies do collapse before paying out their death benefit.

If you have an investable component to a universal life insurance policy, I’d recommend asking about index fund options. Not all policies offer these options, but some do, and they’ll likely be vastly superior to the high-fee mutual funds that are typically offered.

Borrowing From Your Own Insurance Policy – Cash Value and Cash Surrender

My favourite line in the PWL whitepaper that I quoted from above is: The most efficient way of accessing a life insurance asset is through the death benefit, but this, of course, requires dying.

Anything that requires you to die probably isn’t an ideal way to look at the future!

That said, proponents of infinite banking and permanent life insurance are quick to point out that life insurance has benefits for the living as well.

Generally, the pitch goes something along the lines of:

- As you hand money over to the insurance company every year, you will build a cash value within your policy.

- You can withdraw some of this cash value at any time (although it is taxed at that point).

- Instead of withdrawing the cash, simply borrow money from the cash value of your insurance policy. It’s like magic – you “become your own bank” and pay no taxes. Just do this forever and you’ll get rich by never paying taxes.

This “loan money” can come from the insurance company itself, or it can come from a third party. If you borrow from the insurance company, the interest rates are usually quite high. To make matters worse, if the policy loan gets large enough (more than the adjusted cost basis) you can actually be taxed on that loan!

Going the third-party route means that the cash value of your life insurance policy can be used as collateral to access a loan from a lender such as a bank. At the time of publishing, the interest rate for policy loans at RBC was 9.2% (the bank’s prime rate +2%).

FAQ About Canadian Life Insurance for Seniors and Retirees

Summing Up Life Insurance Needs for Retired Canadians

- Life insurance is for protecting people who financially depend on you. If there are no longer people financially depending on you then you almost assuredly don’t need life insurance.

- There are enormous commissions for the folks who sell life insurance. Those commissions are responsible for why the products are pushed so hard.

- If you meet the high net-worth criteria described above, there are still excellent reasons to just invest on your own and avoid the complexity of life insurance contracts.

- The majority of permanent life insurance policies never pay out a death benefit because people stop paying the premiums at a certain point for a variety of reasons. In those cases, you have gotten awful value for your money, as you could have purchased very simple term life insurance instead.

- Guaranteed life and term-to-100 are the cheapest ways to permanently insure yourself for the benefit of your estate. Don’t worry about cash values and all of these other fancy riders.

- In order for life insurance to be even a mediocre investment return relative to DIY investing, you’d have to die young. That way your estate would get the death benefit without you paying into the plan for decades. Anything that requires you to die young probably shouldn’t be a part of your financial plan!

- If you have gotten talked into starting a permanent life insurance plan at some point, it’s probably worth having a conversation with the beneficiary about splitting the costs of the insurance premium each month. Mathematically, it probably makes sense to keep paying the premiums just so the plan doesn’t lapse.

Are You Saving Enough for Retirement?

Canadians Believe They Need a $1.7 Million Nest Egg to Retire

Is Your Retirement On Track?

Become your own financial planner with the first ever online retirement course created exclusively for Canadians.

Try Now With 100% Money Back Guarantee*Data Source: BMO Retirement Survey

I've Completed My Million Dollar Journey. Let Me Guide You Through Yours!

Sign up below to get a copy of our free eBook: Can I Retire Yet?

Buy term and invest the rest!

i agree with your analysis. However, there is a scenario where life insurance is useful but I say the premiums should be paid by the beneficiary.

That scenario is a cash poor estate which has a residential home that the beneficiary (adult child) wants to keep. This adult child also has no money of their own. And has maxed out their credit. I realize there are many other issues etc that need to be addressed in this scenario including whether or not the beneficiary should even attempt to keep the house rather than selling. Suffice to say, I have made and lost that argument.

Had the parent had life insurance in place to cover the outstanding line of credit on the property plus the probate expense, the beneficiary would be able to probate the will in a timely manner. Instead, he can’t pay off the line of credit and therefore can’t probate the house. His vision is that once the house is in his name, he can take a mortgage to cover the LOC and probate but unfortunately the order of transactions is against him. In the meantime, he may use a high interest “estate lender” to facilitate this transaction.

All in all, the entire situation is one where proper planning was not done despite having a will in place.

Hi Susan,

That’s certainly a very specific situation. I suppose a life insurance policy would be one way this situation could have been avoided, but what if instead the individual behind the cash poor estate had opted to simply pay down the HELOC with their years of theoretical insurance premiums? If the estate was left that cash poor, one would assume there wasn’t a lot of extra money lying around each month to pay for a life insurance policy? That said, if there had been a policy in place that was allowed to lapse – then you’re 100% correct, the value there for the beneficiary helping pay the premiums makes a ton of financial sense.

I actually smirked a bit when I read “Suffice to say, I have made and lost that argument” – been there!