Investing Taxes: Dividends, Interest & Capital Gains

Are you curious about how investing taxes are calculated on capital gains, dividends, and interest in Canada?

I’m not a tax expert, but with tax loss harvesting season coming out, I figured it might be a good time to review some of the basics between how Canadian investment returns are taxed in your RRSP, TFSA, and non-registered accounts.

Investing Taxes in an RRSP

Let’s start with RRSPs. As you probably know, RRSP contributions and investment growth are taxable only upon withdrawal.

At that point, RRSP withdrawals are taxed as income at your marginal tax rate at the time. This means that it’s as if you earned the money at a job.

That’s the strategy behind RRSP’s: contribute, let it grow tax-free, and withdraw when you are in a lower tax bracket (hopefully).

The reason that the RRSP works so well as an investment vehicle, is that when you are retired, you will typically be in the lower tax brackets (unless you have a very large portfolio and/or a generous pension). Because of this, you’re able to invest money now before it is taxed while you are at a high tax bracket, and withdraw it when you are in the lowest tax bracket (i.e. retired).

Investing Taxes in a TFSA

The main benefit of the TFSA is that you don’t have to worry about paying investing taxes on anything that you hold within it.

When you contribute to a TFSA, you are doing so with after-tax dollars, meaning that taxes have already been paid by you, on those amounts.

In other words, even if your investments quadrupled in value within your TFSA, you still wouldn’t pay any tax on those gains. You also wouldn’t pay any tax on the dividend or interest income that you may have earned within your TFSA.

Because of this tax efficiency, a common practice when it comes to the TFSA, is to use it for the investments that you think will grow the most, since in the future you’ll be able to take those investments and gains out tax-free.

Investing Taxes in Non-Registered Accounts (Taxable Accounts)

Now on to Non-registered accounts. This is where things can get a bit tricky. There are 3 types of taxes that you need to consider.

- Capital gains tax (preferred)

- Dividend tax from Canadian corporations (preferred)

- Interest tax and dividends from non-Canadian corporations

Investing Tax on Capital Gains

When you profit from selling a stock in a non-registered account, you will be subject to capital gains tax. What are capital gains? A capital gain is the difference between the selling price and buying price of a stock – less the commission.

For example, if you sold a stock for $1,000 (inc selling fee) and paid $800 (inc buying fee), you would have a capital gain of $200.

Capital gains tax is subject to a 50% inclusion rate. This means that 50% of your profit will be included as income.

So in our above example, $100 would be added to your income and taxed at your marginal tax rate. Or another way to look at it, is that any profits from a stock sale in a non-registered account are taxed at HALF your normal marginal rate.

Obviously that’s a lot better than getting taxes at your full marginal rate (as if you had earned the money at a job).Some Canadian investing tax experts argue that any part of your non-registered investment portfolio that produces interest income such as bonds or GICs should be placed inside a TFSA or RRSP in order to protect that income – due to the fact that it is taxed at 100% of your marginal tax rate.

This stance is a lot harder to debate in 2023 as interest rates have shot through the roof. Check out our Best GIC Rates in Canada article for the latest on where to get risk-free investment return. At press time, 5.65% was still available! When your GICs and bonds are generating that sort of return, it’s tough to argue that they should take priority when it comes to room under the tax shelter umbrella.

Now prior to 2023 I would have said not to worry about sheltering such paltry gains due to interest rates being so low. At that time I prioritized my equities when it came to space in my registered accounts. You can also read the article I wrote a few weeks ago for more information on how to organize your investments if you’ve maxed out your RRSP and TFSA.

One additional advantage of keeping your capital-appreciating stocks outside of an RRSP is because you can claim your losses against your gains to reduce your taxes payable. Whereas within an RRSP, losses cannot be claimed.

For example:

If in 2023 you sold stocks for a $4,000 non-registered portfolio profit and sold other stocks that generated $1,000 in losses, your total profit is now $3,000. To figure out your taxes payable, it would be: $3,000 x 0.50 = $1,500. This $1,500 would be added to your taxable income for that year and taxed at your marginal tax rate.

This is why you’ll read some tax strategies to sell your losing stocks at the end of the year. The losing amount will be deducted from your total winning amount and reduce your overall taxes. This strategy is known as tax loss harvesting.

What if you have a losing stock(s) for the year, but you believe it’s a long-term winner? You’re probably thinking to sell it before the end of the year and purchase it again. Not so fast, you have to make sure you don’t violate the superficial loss rule.

What is the Superficial Loss Rule?

According to the Government of Canada’s explanation, This rule applies where a person or affiliated person acquires or had the right to acquire the same or identical property within 30 days after the disposition or 30 days before the disposition of the property in question. The disposition could have been made to anyone. In these cases, the loss on the disposition is denied and the amount of the loss is added to the cost of the substituted property.

In layman’s terms, it simply means that if you sell a stock at a loss, you can’t repurchase the shares back again within 30 days and claim the loss against your gains. However, if you do repurchase the same shares back within 30 days and you profit from it in the future, you can deduct the initial loss against your gain of THAT stock.

For example:

- Purchase 10 ABC stock for a total cost of $1000

- Sell 10 ABC stock for: $800

- Loss: $200

- Repurchase 10 ABC stock within 30 days for: $850

- Sell 10 ABC stock in the future for $1200:

- Profit: $1200-$850-200 (initial loss) = $150

- Taxable Amount: $75 ($150 *50%)

As a side note, you should consider the superficial loss rule if you are attempting the Smith Manoeuvre (SM) or want to hold Canadian dividend stocks outside of your TFSA and/or RRSP. The SM suggests to sell your non-reg stock to pay down your house, then REPURCHASE the stocks. If you sell stock at a loss, you should wait 30 days before repurchasing. Otherwise, the loss will be omitted.

Optimize Your Taxes and Make Sure You are Ready For Retirement

Our very own Kyle Prevost has created an online course where he dives deep and teaches you how to optimize your savings in multiple ways.

Are You Saving Enough for Retirement?

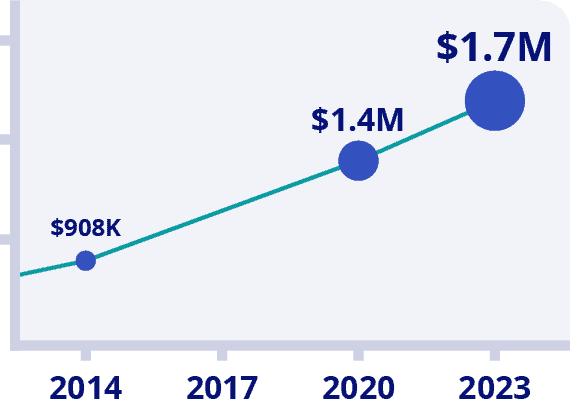

Canadians Believe They Need a $1.7 Million Nest Egg to Retire

Is Your Retirement On Track?

Become your own financial planner with the first ever online retirement course created exclusively for Canadians.

Try Now With 100% Money Back Guarantee*Data Source: BMO Retirement Survey

Capital Gains and Dividend Tax

Dividends are payments that a corporation makes to its shareholders. When we’re talking about most companies on stock exchanges, dividends are paid quarterly (every three months). Dividends will show up in your online brokerage account when the company pays them out.

Capital gains on the other hand are when you make a profit from selling an asset for more than you paid for it. Capital gains can be calculated on land, businesses, gold, paintings – pretty much any investable asset. To calculate your capital gain on a stock, you subtract what you paid for it, from the money you got when you sold the stock to someone else.

How are Dividends Taxed in Canada?

The process by which dividends are taxed in Canada is a bit confusing. First off, let’s note that we’re talking about dividends from the stock market, NOT dividends from your own private corporations (called Canadian Controlled Private Corporations – or CCPCs).

When Canadian dividends are in a TFSA or RRSP they are not taxed. If you get dividends from a company outside of Canada, then it is a bit more complicated because you have to factor in the home country’s withholding tax policy as well.

When Canadian dividends are paid into a non-registered brokerage account, they are subjected to a process called a gross up, and then the dividend tax credit is applied. An in-depth example is provided below.

How are Capital Gains Taxed in Canada?

Capital gains in Canada are not taxed if they are within a TFSA or RRSP. In a non-registered brokerage account, capital gains are taxed at 50% of your marginal tax rate.

Should I Reinvest Dividends and Capital Gains?

If you don’t need the liquid cash in your bank account to pay for day-to-day expenses, then reinvesting your dividends and capital gains is a great way to build wealth. This is especially true if your dividends and capital gains are within an RRSP or TFSA.

How Much Dividend Income is Tax-Free in Canada?

Dividend income is all tax free if it is within an TFSA or RRSP. If we are talking about Canadian dividend income in a non-registered account, then one has to take into account the provincial and federal dividend tax credits. I’ll describe the math behind the dividend gross up and then applying the dividend tax credits below.

Long story short, if you have no other income other than eligible dividends from Canadian companies in your brokerage account, then you can receive about $54,400 tax-free from the federal government. Once you go above that amount, you’re going to get hit with the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

Now, depending what province you live in, the amount of dividend income that is tax free will differ. In most provinces you won’t owe much in taxes until that $50,000 mark. Keep in mind, both you AND your partner can withdraw that much dividend income tax free from your brokerage accounts in a given tax year.

What’s the Dividend Tax Rate in Canada?

The dividend tax rate in Canada ranges from 0% to over 50% once you combine the federal tax and the provincial tax. As described above, you need to understand how the dividend gross up and dividend tax credits work in regards to eligible dividends to find your specific dividend tax rate.

Also, keep in mind that dividends are not taxed separately from your other income. Instead, all sources of income must be taken into consideration when looking at your overall tax rate payable.

Is There a Dividend Tax in my RRSP or TFSA?

There is no dividend tax in your RRSP or TFSA on Canadian eligible dividends. Canadian eligible dividends are the dividends that go into your brokerage account when they are paid out by large Canadian companies.

If you have dividends paid from other countries in your RRSP or TFSA, then a withholding tax might have been applied to those dividends before they arrived in your brokerage account.

Are Dividends Included in Capital Gains?

Dividends are not included in capital gains unless you are referring to swap-based ETFs such as HXT or HXS.

Investing Taxes on Dividends and the Dividend Tax Credit

Why are dividends tax efficient to shareholders?

Dividends are tax efficient for shareholders because distributions are paid out with after-tax corporate dollars. Meaning that the company pays out the dividend distributions AFTER it has paid all of its taxes to the government.

This is the reason why when you receive a dividend payment from a Canadian public company in a taxable account (i.e. a non-registered account), you are eligible for the enhanced dividend tax credit.

How do I calculate the dividend tax and dividend tax credit?

With the enhanced dividend tax credit, gross-up any dividends that you receive (from a Canadian public corp) for the year by multiplying it by 38% (2023).

- Ex: $1000 dividends received in 2023 * 38% = $1,380

You add this amount to your income for the year. You take this total amount and figure out your marginal tax rate.

- Ex. $55k + $1,380 = $56,380

Multiply your grossed-up amount by your marginal tax rate to figure out total taxes owed.

- $1,380 * 29.65% = $409.17 (for this example we’re using the combined federal and Ontario tax rate/bracket which is 29.65% for 2023)

Calculate Federal Tax Credit and Provincial Tax Credit

- $1,380 * 15.02% (Federal rate) = $207.28

- $1,380 * 10% (ON) = $138

- Total tax payable on $1,000 worth of dividends: $409.17 – $207.28 – $138 = $63.89.

- Or, you can go on the web and calculate it yourself.

How about dividends from foreign companies?

Dividends received from foreign companies do NOT qualify for the dividend tax credit and are 100% taxable. For all intents and purposes, you can treat foreign dividend income the same as interest income or income you earned at a job.

Investing Tax on Interest Income (In a Taxable Account)

What is interest income?

Interest income is interest received from GICs, high-interest savings accounts, bonds, and private loans.

How is interest taxed in a non-registered (taxable) account?

Interest income is 100% taxable. This means that if you earn $1,000 in interest for the year, $1,000 is added to your income and taxed at your marginal rate. (40% tax rate = $400 to be paid in taxes – OUCH!)

In other words, it’s just like you earned the money at a job.

How to Calculate US Capital Gains Tax in a Non-Registered Account

Another common question is how to calculate capital gains tax on US traded stocks within a Canadian non-registered account (in USD).

While the calculations are very similar to trading Canadian stocks, the difference is that the currency exchange needs to be accounted for.

Basically, the buy price and sell price need to be converted to Canadian dollars first prior to calculating capital gains.

Once capital gains after foreign exchange are calculated, the same 50% inclusion rate is used.

To figure out the exchange rate on the day of the trade, the Bank of Canada website has all the forex history you need.

Here’s an example:

- Stock: XYZ on NYSE

- Buy Price USD: $10 x 100 shares = $1,000

- Buy CAD/USD Exchange: 1.41 (on day of buy trade)

- Buy CAD: $1,410

- Sell Price USD: $15 x 100 shares = $1,500

- Sell CAD/USD: 1.43 (on day of sell trade)

- Sell CAD: $2,145

- Capital Gain: $730 minus commissions

- Capital Gains Tax: ($730 minus commissions) x 50% x marginal tax rate

In the above example, if it was simply a stock on the TSX, then the capital gain would be $500 (minus commissions). However, since there may be a loss or gain due to the value and volatility of the USD currency itself, it can work in favour or against the investor.

Another method my accountant told me about is to use an average USD/CAD exchange for all the transactions to avoid looking up the exchange rate on the day of the trade for every transaction. While this may simplify things, you’ll need to work through the numbers yourself to see which option reduces capital gains the most. For a frequent trader, I can see how using a single annual average forex rate can be advantageous.

Personally, to keep things simple, I hold US securities in registered accounts. As per my article on portfolio allocation, US dividends stocks are kept in an RRSP to avoid the withholding tax on the dividends and the occasional USD trade may be made within my TFSA.

Reduce your Investing Taxes by Claiming your Capital Loss

What is a capital loss?

It’s simply where you sell a stock in your non-registered portfolio for a loss.

From here, it just seems like a loss, but there is a bright side. Unlike investments within your RRSP (or TFSA), capital losses within a non-registered portfolio can be claimed against your capital gains for the year (or previous years).

Here are some important facts about capital losses:

- Capital losses can only be claimed on investments within taxable investment accounts (also known as non-registered accounts).

- Only 50% of capital losses can be claimed.

- Capital losses can be claimed against capital gains in the current year, up to 3 previous years or carried forward indefinitely. However, it can be claimed against income on the year of the taxpayer’s death (comforting hey?).

- Tax loss selling must be made before December 24 of that year as it takes 3 days to settle the trade.

How Tax Loss Selling Works – An Example

Say for example Jim (@ 40% marginal tax rate) had $10,000 in capital gains in 2023, but also $4,000 in capital losses. What is the resulting tax payable?

There are two ways to calculate this, both of which turn out with the same result:

- $10,000 – $4,000 = $6,000 x 50% x 40% = $1,200 tax payable

- $10,000 x 50% X 40% = $2,000 capital gains tax; $4,000 X 50% X 40% = $800 capital loss claim; result = $1,200 tax payable.

The last question is why would you sell for a tax loss? The main reason for this, is that sometimes at the end of the year, you realize that you’ve made some bad stock picks that have a low probability of recovering. Why not dump the losers, claim the tax deduction and move on?

What about tax-loss selling or tax-loss harvesting for index investors?

Keep in mind that tax-loss selling primarily applies to investors that pick individual stocks within a taxable account.

It doesn’t apply as much to index investors since as an index investor, you are buying and holding the entire index long-term. You don’t have any “losers” per se, since you aren’t actually trying to pick the winning stocks and avoid the losing stocks (i.e. as an index investor, you are just buying all the winners and the losers).

If an index experienced losses in the year, then you also have to be careful about the superficial loss rule mentioned earlier.

For example, if the S&P/TSX index (the main Canadian index) fell in a given year, you can’t just sell that ETF to claim a capital loss, and then buy it again immediately.

It also looks highly suspicious to the CRA if you sell an index from one provider (ex. Vanguard) and then buy the same index ETF through another provider like iShares. In that case, you are still technically re-buying the same index, and so I seriously doubt that the CRA would rule in your favour as it clearly appears that you are doing this just to minimize taxes.

What you can do (and the CRA has not spoken out against this to the best of my knowledge) is buy a similar ETF to the one that you just sold – then 30 days later, sell that ETF and buy the one that you really want (and had originally). There is no reason to over-complicate your life with stuff like this unless your overall portfolio is large enough that the loss that you experienced represents a decent tax write off. If you are sticking to investing only in your RRSP and/or TFSA, then obviously this strategy doesn’t apply to you.

To summarize, tax-loss selling is a strategy that can be great for investors who at one point picked an individual stock(s) or ETF that they thought would do well, yet after some time realized that they made a mistake, and would now like to sell it and move on.

It’s also worth mentioning that for investors that want to keep their life super-simple, our Wealthsimple Review explains how Canada’s #1 robo advisor will actually complete this “tax loss harvesting” on your behalf once you have $100,000 in assets with the company.

However, the strategy can also be used effectively by index investors who have a large enough portfolio and a large enough loss in any given tax year to justify “booking” or “making real” a paper loss in their non-registered account in order to reduce their taxes owing.

Our all in one ETFs article shows some excellent options for folks that like the idea of claiming a tax loss in their non-registered account, but also value overall simplicity. That said, remember to read the fine print when booking a transaction like this.

Hello,

I have a question regarding taxation on selling the same stock in two different brokerages. If I sold each stock on the same day. Will the sale of these stocks generate capital gains or regular “business” income?

Hi Nathan – while I’m no tax accountant, I’m fairly certain that buying and selling of the same stock within two brokerages is treated exactly the same as if bought and sold within one brokerage. Track your buys and sells (therefore ACB) by stock with no value placed on where it’s bought/sold.

does CRA use the ‘first in first out’ principle for determining the Cost Base for share purchases? For example, if you purchase 500 shares ABC at $50ea and 500 shares of same stock later on at $80ea, followed by selling 600 shares of ABC at $100 each, would your proceeds be computed as: 600 x $100 and your costs computed as: 500x$50 +100x$80 or $33,000 for a net gain of $27,000.

My friend uses the average cost principle and I am doubtful of this approach.

With their calculation, they would report proceeds of 600x$100 (60,000) less the average cost of $65 each (600x$65) or $39,000 resulting in a net gain of $21,000. Of course, my friend would have to remember that the value of remaining 400 shares would be at the ‘average’ price of $65 and any subsequent gain would have to be calculated at that base cost (which would be pretty difficult to track in my opinion).

In Canada, your friend is correct in using the average cost principle. That’s how my brokerage provides it to me for tax purposes. No protest from CRA and been doing that for many years.

Instead of taking my RRSP payment I opened a regular stock account and transfered all of the payment including cash an stocks into it. I paid tax each year on my RRSP amount. I have now got cash sitting in this regular account that I would like to withdraw. Do I have to pay tax on this money which I already paid tax on before?

Hi Mary, if you are referring to a non-registered account, then you can withdraw cash from the account without paying tax. However, if you had capital gains in the account, you will owe taxes when you file your tax return.

My question is regarding the superficial loss rule. Are losses only unclaimable when you buy back the same security within 30 days after sale. Or is it also unclaimable if you sell within 30 days after buying. I’ve heard it’s realy a 60 day rule, 30 days before and 30 after. Can you please comment. Thanks.

I’m in something similar to the Smith Manoeuvre. I have a HeLOC and I pay into Segregated funds every month and the interest only payments. As my funds build up in value, eventually, I can cash out and pay off my home. My question is… How do I know what my Tax Hit will be before I cash out? someone said to cash out $30,000 for the next 5 years to minimize Capital Gains Tax? Can you tell me how I would figure out the Tax Hit? I guess I go back to the holder of my Seg Funds and ask them? Both my fund mgr and the holder of the funds said my taxes would be approx. $6,000 on withdrawal of $30K…. when I got my T-3, the capital gains was like $14K! what gives? How do I find out what my taxes on capital gains will be? I’d like to cash out totally but I’m afraid of the Tax Hit.

Thanks

Wayne.

HI Folks, I have a quick question – I have a capital loss that I’m carrying of around 11k, I’m going to sell some stock options I have creating a capital gain, is the loss applied against the gain only, or on total amount of the share options excersied? An example would be:

I excercise 40K in share options and recieve 30K in net cash (50% of 40K is 20K taxed at 50% = 10K in tax). Would my capital loss of 11K be applied against the 20K in capital gain gross ie my 20K becomes 10K and I now only owe 5K in capital gains tax?

Mike, the adjusted cost base of the shares is affected each time you buy more shares. If you continue to buy shares and the price per share goes down, then this will decrease your ACB. And subsequently affect any gains you may have. When you eventually sell, the gains and losses are calculated using the adjusted cost base. Think of all the shares going into a cost “pool” in which the cost is adjusted every time you buy more shares of the same company.

When you do sell the shares the taxes you pay will be based on your marginal tax rate. Any capital gains will be included in your income for that year (50%). The other 50% of the gain is not taxable.

Let’s assume that I buy 100 shares of the same stock each month for 25 years, and plan to sell them for retirement income as needed. It’s safe to assume that the price per share will change month by month, or year by year.

In 25 years from now when I start selling portions of my portfolio for retirement income, how do I know what price I paid for the portion of shares I’m selling?

Thanks,

Mike

@Dan, it’s never a bad thing to pay less tax! However, you also need to look at the big picture and if you would sell the investment at all if it weren’t for the tax consequences.

Thanks FT,

I do like some of the investments but will definitely get rid some of it.

Consideration to liquidate or not was more for the tax purposes since this year my marginal tax will be at lower rate. I thought it would be a good idea to realize the gain. But I am not sure if that will actually matter.

Thank you.