Investing Inside a Corporation for Retirement in Canada

Before you jump into the details of investing inside of a corporation for your retirement, it’s likely worth taking a few minutes to read my articles on paying yourself from your corporation with salary vs dividends, as well as how corporate taxes work in Canada and how to use Horizons Swap ETFs to lower your corporate tax bill (more on these later in the show).

I also want to highlight the fact that this article ended up basically turning into a mini-eBook, and I actually had to update it before publishing to include the New Capital Gains Rules in Canada as a result of the 2024 budget coming out.

This was a pretty big change for people investing within a Canadian corporation and I will continue to update this article as the full impact of the new tax rules gets fleshed out. Just because something is included in the budget, it doesn’t mean it will be passed into law, or that fine-tuning won’t be done to the proposals.

I included a section at the end of this article that gives my early take on how the new capital gains rules will result in different tradeoffs for those investing in their Canadian-controlled private corporation (CCPC).

Withdrawing funds from your CCPC small business each year can be somewhat complicated, even if you have a relatively simple corporation where you transfer all of your profit over to your personal accounts each year. We covered that adventure last week.

But once we decide to start investing inside of our corporation – instead of taking all the money out each year and using it to invest within our RRSP and TFSA (or other personal accounts) – the complexity gets dialed up quite a bit.

- Can I Save for Retirement In My Company?

- Saving and Investing Inside vs Outside of Your Corporation (in a non-registered account)

- What About the $50,000 limit for CCPCs and the Small Business Deduction?

- Corporate Accounts: Passive Income Within a Corporation

- When Should I Take My Investments Out of My Corporation?

- What Happens to My Corporation After I Retire?

- New Capital Gains Rules for Canadian Corporations

- Investing Within My CCPC – FAQ

- So Should I Start Investing Inside My Corporation or Not?

I want to point out two things here before we go any further.

1) I don’t tackle this stuff on my own when it comes to my wife and I’s CCPC(s). I write about it and can draw a diagram on what our overall cash flow strategy looks like – BUT I still want someone else to look it over for me. We have a few smaller corporations, nothing especially large or complicated, but making it all work together – along with our personal income tax decisions – can make a person question their sanity at times.

I want an expert to look this stuff over. Someone whose full-time job it is to be up to date with that latest passive income rules the CRA creates for corporations. Someone who isn’t going to waste my time trying to sell me expensive insurance products or mutual funds.

That’s why I recommend Jason Heath and his team at Objective Financial Partners. Don’t take my word for it – Google Jason’s name to see why he is such a highly-regarded fee-only financial planner.

2) When I write about “saving and investing within my corporation” for the rest of this article, what I’m referring to is taking retained profits (which is what is left after paying expenses, salaries, and dividends) and using that money to buy investments (aka: building a retirement portfolio). Generally speaking, that means opening up a corporate investment brokerage account to buy and sell stocks and ETFs. It can also mean buying other types of investments – but we’ll tackle those another day.

I’m NOT talking about “re-investing money into my corporation” in the sense of buying new equipment for my company, or saving money in a high interest savings account so that I can upgrade my company’s software next year.

This is all about using your Canadian corporation to invest for retirement. And yes, as I said, it can be a bit tricky, but you can also increase your net worth by a substantial amount if your company is quite profitable and you handle the investments within the corporation correctly.

Some business owners are not aware they can even use their cash savings in their corporation to buy investments. They can and they most certainly should consider it as part of their overall long-term plan.

Can I Save for Retirement In My Company?

So why would you want to use your CCPC to save for retirement?

That’s what you have an RRSP and a TFSA for right?

Most people who are considering investing within their CCPC for their eventual retirement are probably making enough money that they can afford to max out their TFSA, maybe their RRSP as well, plus pay for life’s expenses – and still have money left over at the end of the day.

For these business owners, here is a potential scenario:

- My company made $180,000 in profit this year.

- I decided to pay myself $100,000 in salary ($8,333.33 per month). That’s enough to pay my mortgage, buy the groceries, make my TFSA contribution, and then pay the rest of the bills.

- I’ve got $80,000 left that I want to invest for retirement.

- Depending what I do with that $80,000, I may have to pay corporate tax on that profit. If I pay extra salary (or a year-end bonus), that is tax deductible to the corporation and reduces its taxable income. Corporate tax is generally payable on active business income at between 8% and 16%.

- Should I take the profit out of my corporation (in dividends or salary) and invest it within my RRSP and/or a personal non-registered account?

- Or – should I instead, leave it in my corporation, open a corporate brokerage account, and then start investing for retirement there?

We’ll address the RRSP vs corporate investing account comparison at some point, but for now, I want to make it crystal clear why someone would bother with all of this trouble:

By investing for retirement within your corporation you can potentially end up with a much larger nest egg when you retire, compared to if you took all of the money out of your corporation each year!

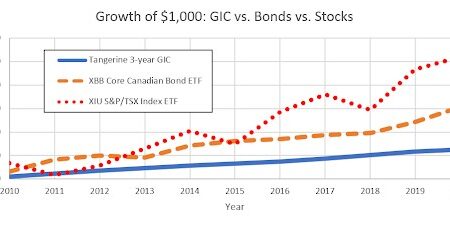

The key concept to understand here is tax deferral. In many cases (again – this depends on personal circumstances and province of residence) your corporate tax rate is going to be substantially lower than if you took money out of the corporation and paid a high personal income tax rate on it. For a high income earner, there could be 40%+ tax deferral.

That means that more money will be left to buy investments in a given year. If those investments are left alone to grow for a few decades – until they are withdrawn in retirement – that initial difference in how much you had to invest after taxes may have multiplied into a lot of money. In this case, you’d have a substantially larger investment portfolio held within your corporation than you would if you had taken the money out and invested it in a personal non-registered account.

Now, you would have to pay income taxes (and just how much you would have to pay, we’ll get to in a second) whenever you sold those investments and moved the money outside of your corporation. BUT – the key thing to understand here is that you are in control of the exact amount of income you want to take out of the company every year.

With proper planning, this will usually result in a lower tax rate than you would have paid back when you were actively running your corporation and making “the big bucks” (oftentimes taking out money to pay for a mortgage, young family expenses, etc).

I’ve personally seen cases where this type of long-term corporate tax planning for investments within the CCPC will save the business owners hundreds of thousands of dollars and leave a substantially larger nest egg to their estate.

Saving and Investing Inside vs Outside of Your Corporation (in a non-registered account)

| Consideration | Inside The Corporation | Outside The Corporation |

| Taxation of passive income | Passive income taxed at corporate rates. Only 50% of capital gains are taxable, though the 2024 federal budget has proposed increasing this to 67%. Investment income may be subject to refundable tax that is returned to the corporation when it pays taxable dividends to shareholders. | Personal tax rates apply. 50% of capital gains are taxable, though the 2024 federal budget has proposed increasing this to 67% for personal capital gains exceeding $250,000. Eligible dividends and capital gains benefit from preferential tax treatment. |

| Amount of your corporate profit left to buy investments and grow over time | reinvestment of funds without immediate personal tax, only paying relatively low corporate tax rates on business profit. | Higher personal tax rates payable on corporate withdrawals, potentially reducing the available amount. |

| Passive income limitation | Exceeding $50,000 of passive income from investments can reduce the Small Business Deduction, potentially increasing tax rates on active business income. | Investing outside the corporation does not impact the corporation’s small business tax rate. |

| Retirement planning | Corporate-owned life insurance and Individual Pension Plans (IPPs) are options for tax-efficient investing. | Access to RRSPs and TFSAs, which offer tax-deferred growth and tax-free withdrawals within contribution limits. |

| Estate planning and succession | Efficient transfer of assets through an estate freeze or use of the Capital Dividend Account (CDA) for tax-free distributions. | Personal assets may incur probate and high taxes upon death. RRSP and non-registered accounts can be transferred tax-deferred to a spouse but are taxable when left to non-spouse beneficiaries. TFSAs can be left to anyone tax-free. |

| Income sprinkling | Limited opportunities to split income among family members through dividends, subject to tax on split income (TOSI) rules. Lifetime capital gains exemptions can be utilized for multiple family members if a business may be sold. | Includes spousal loans, spousal RRSPs, discretionary family trusts, and pension income splitting of RRIF and eligible pension income in retirement. |

| Asset protection | Corporate structure can provide creditor protection for investments, depending on corporate and legal setup. | Personal investments are generally more exposed to personal creditors, with exceptions for registered accounts under certain conditions. |

| Compliance and administrative costs | Higher due to the need for corporate tax filings and the management of corporate investment accounts. | Lower, as investments are held personally and are subject to simpler reporting requirements. |

| Impact on government benefits | Strategy to minimize personal income can preserve eligibility for income-tested benefits and credits. | Personal investment income may affect eligibility for income-tested benefits and tax credits, depending on the investment income level. |

What About the $50,000 limit for CCPCs and the Small Business Deduction?

One of the first things that owners of a CCPC will read about when they look up information on investing within a corporation are a lot of headlines about a “$50,000 limit on passive income for a CCPC.”

This type of headline is a good example of nerdy clickbait that distorts the truth. For most owners of a CCPC this $50,000 figure is never going to apply to you. If you’re at the beginning of a career, spend most of your corporate profits on life expenses every year, or just haven’t built up a big investment portfolio within your corporation, then you’re not going to be affected by this legislation. I’ll do my best here to sum it up as succinctly as possible:

- In 2017, the government passed new rules in regards to investing within your corporation that began in 2018. The basic aim of the new rules was to make sure corporation owners didn’t get to use their business as sort of an “unlimited RRSP.”

- Remember, when your company makes money in its normal course of business every year, that’s called operating income. None of that income applies to the passive income $50,000 threshold.

- When your company makes an operating profit, pays tax, then pays dividends (or not), it might still have money left over within the corporation – that’s called retained profits. If the retained profit is then put into a corporate investment account (for example at an online brokerage) and used to buy stocks, ETFs, or other investments, then the growth of that money is going to be passive income.

- When I say “the growth of that money” I’m specifically referring to capital gains, dividends from Canadian stocks, dividends from stocks based outside of Canada, and interest. All of those different types of income are collectively called “passive income” when held inside a corporation – BUT each will have different tax considerations, as we’ll soon see.

- There are also separate considerations for purchasing real estate investments within a corporation, but that’s a discussion for another day.

- If the combined amount of passive income from those investments goes over $50,000 in a given year, then it is going to have a limiting effect on your Small Business Tax Deduction.

- If you recall from my original corporate tax explainer article, the Small Business Deduction is the lower rate of tax that CCPCs get to pay on their first $500,000 in business income. That’s obviously a tax advantage that most folks want to be aware of.

- When you earn passive income above the $50,000 threshold, the CRA is basically going to say, “Hey, you’re making too much money to pay these low tax rates. What we’re going to do is reduce the amount of your Small Business Deduction by $5 for every $1 in passive income you make over that $50,000 threshold.”

- Now, this reduction in the $500,000 SBD isn’t the end of the world. Making $500,000 in corporate profit every year isn’t easy. Paying a higher corporate tax rate on the amount you’re making over the lower threshold isn’t a massive deal since you can now pay yourself in eligible dividends instead of non-eligible dividends.

Let’s take a look at an example:

Olga the Owner had a great year, and Olga’s Ornaments (her CCPC) made $600,000 in operating profits. Olga has decided to invest within her corporation, and has built a sizable investment portfolio – which generated $70,000 in passive income for the year.

In this situation, if the business owner paid themselves no salary, the math would go something along the lines of:

- Olga’s is $20,000 over her $50,000 passive income threshold.

- Olga will now see $100,000 evaporate from her Small Business Deduction.

- As a consequence, Olga will now have to pay the higher rate of general corporate tax on $200,000, because only $400,000 will qualify for the Small Business Deduction instead of $500,000.

But wait… If Olga were to pay herself a $200,000 salary, (which Olga knows is probably a good idea, because she read our article a few weeks ago) Olga’s corporation would then only have made $400,000 in after-tax profits. Consequently, the reduced Small Business Deduction won’t matter. All $400,000 will qualify for the lower tax rate.

It’s worth noting that most small business owners (at least the ones that use smart corporate tax planning) are not going to generate $70,000+ in passive income within their corporate investing account each year. This is because capital gains only come into play when you sell an asset such as a stock or ETF. Even if Olga had a sizable corporate investing account, it might look something like this:

| Amount Olga Initially Bought the Investment For (“Adjusted Cost Base”) | What the Investment is Currently Worth | Amount of Dividends or Interest Generated This Year | |

| Equities | |||

| 18% HXT | $500,000 | $720,000 | $0 |

| 24% HXS | $500,000 | $960,000 | $0 |

| 18% HXDM | $500,000 | $720,000 | $0 |

| Bonds | |||

| 40% ZAG | $1,600,000 | 1,600,000 | $54,000 |

In this situation, Olga’s investments have increased in value by almost a million dollars since she bought them – BUT this is not relevant for her yearly passive income threshold. That increase in value doesn’t become recorded passive income until she sells the ETFs (when they would become capital gains). The only passive income Olga would worry about with this portfolio for the current year was the $54,000 her ZAG ETF generated in interest payments. Olga could eliminate this amount completely by switching from the ZAG ETF to the HBB ETF.

Alternatively, Olga could actually completely eliminate her annually-generated passive income by putting her dividend-bearing and interest-bearing investments in her RRSP or TFSA (outside her corporate account). This way she could go with 100% equities in her corporate account, and use the above combination of Horizons Total Return ETFs and other ETFs to generate $0 in passive income – or very close to $50,000 in passive income (if she opted to take some dividends instead of using only total-return ETFs).

Olga would have to balance out her future withdrawal plans (she will eventually have to pay tax on those capital gains when she sells the ETFs and withdraws the money) with her current desire to pay the lowest amount of tax possible.

In any case, it’s easy to get too bogged down in the minutiae of the $50,000 passive income threshold. There are usually bigger fish to fry when it comes to tax and investment planning for a high-earning CCPC.

Corporate Accounts: Passive Income Within a Corporation

Let’s get one thing straight right off the bat here: Corporate accounting is a pain in the butt.

It’s just very complicated – especially once you start making (and saving) substantially more money than the average Canadian, and really insist on getting the most after taxes. If you really want an in-depth understanding of how much tax you will pay – and save – by investing within a corporation, there isn’t really a short cut.

Remember: We’re not talking about operating business income here. This complexity is a result of dealing with the passive income that is created when you invest within your corporation.

We’re going to focus on the four main types of income you can get as an investor:

1) You invest in a stock or an ETF (not a mutual fund because you’ve read our all-in-one ETFs article and understand why that’s a bad idea) and then eventually sell it for more than you bought it for. This is called a capital gain.

2) You invest in a stock or an ETF that is completely made up of Canadian companies and it pays your corporate investment account an eligible dividend.

3) You invest in a stock or an ETF that is made up of companies from outside of Canada, and it pays your corporate investment account foreign dividends.

4) You invest in a bond ETF or a GIC or a cash ETF or a high interest savings account. Those investments pay you interest.

While you can absolutely invest in real estate within your corporation, I’m going to save that topic for another day, as it deserves its own article.

Ok, so we’re investing inside our corporation with the long-term goal of building a nest egg for retirement – how do we keep track of the money we make from interest, dividends, and capital gains?

Basically, accountants needed a way to keep track of the different types of passive income that you’re earning inside of your corporation, because each of those different types of income we just described above has to be handled differently when it comes to tax integration. To put it another way, each of those different types of income will be taxed differently when you pull it out of your corporation in order to spend it on life (whether that’s during retirement or any other time).

Consequently, accountants create “make believe accounts” in order to keep track of all of this.

I know – “make believe accounts” sounds insane – but I’m just not sure what else to call these things.

Some people call them “notional accounts”. Others call them “non-real accounts.” What you really need to understand is that these accounts are created for record-keeping purposes so that you pay the appropriate amount of tax when you take the money out.

So – let’s take a look at what these “notional, make-believe, corporate accounts” have to do with investing for our retirement.

The Capital Dividend Account (CDA)

You sell a stock or an ETF that you had purchased as an investment within your corporation – now what?

First off – the original amount of money that was used to buy that stock or ETF has already had corporate tax paid on it. That money can be transferred from the corporation over to your personal spending account in the same manner as any other corporate income, and you might want to review my article in regards to how corporate dividends vs salary would go for you.

The more complicated consideration is the amount of profit that you made if the stock or ETF has increased in value since you purchased it. Once again, that amount is referred to as a capital gain.

If you sold a stock or ETF outside of your corporation, in a non-registered personal brokerage account, you would only pay tax on 50% of your capital gain. In other words, if you bought a stock for $50, then ten years later sold it for $100, you would have a $50 capital gain. When you calculate your income taxes you would essentially add in $25 of taxable income.

Within a corporation, you can sell a stock or an ETF, and “realize” the capital gain – but you do not have to take the money out of the corporation right away. As of June 25, 2024, corporations now pay a higher capital gains inclusion rate of 66.67%. Because of that ability to keep the capital gain within the corporation, we need to track that tax-free 33.33% of the money, as well as the 66.67% of the capital gain that is taxable. The tax-free 33.33% of the capital gain is tracked by the Capital Dividend Account (CDA).

If you want to take money out of your corporation in a given year – but don’t want any more taxable income (perhaps you are in the highest tax bracket already) – then you can withdraw your CDA money without paying any taxes on it. In order to do this, you would file a special election to issue a tax-free capital dividend.

Now before you get too excited about this tax-free withdrawal stuff, remember that the remaining profit that you received from selling the stock or ETF is fully taxable in the corporation.

The Refundable Dividend Tax on Hand (RDTOH) Account

Perhaps the most difficult part of investing within a Canadian corporation is how dividends from the investment portfolio are handled. It took me a couple of tries to get my head around this one – and the “best practices” in regards to this account aren’t easy to figure out either.

One again, all of this complication comes back to the concept of tax integration between corporations and individuals.

Because the government wants to discourage folks from using their corporations as “unlimited RRSPs” they’ve put a big tax on dividend income and interest income. That tax is basically equivalent to the highest possible personal tax rates in Canada (50%-ish).

Ok – now before I lose you – you’re going to see the word “dividend” a lot here. I have to use it to refer to the dividend payments that your stocks or ETFs are paying to you inside of your corporate discount brokerage account.

I also have to use the phrase “eligible dividend” and “non-eligible dividend” when I talk about taking money out of your corporation, and moving it over to your personal spending accounts. I hope that makes sense – it’s the same word, but now that you’re using your CCPC to invest in larger corporations from around the world, you are going to have at least two layers of dividends to consider.

Now – back to how dividends will be taxed if we choose to invest within our corporations. That very high tax rate will be applied – BUT – we can largely nullify that large tax rate if we pay ourselves a dividend each year. For CCPCs with under $500,000 in annual net business income, these will generally be non-eligible dividends, but for CCPCs that use up all of the small business deduction space, there may be eligible dividends that can be paid.

When we pay ourselves a non-eligible or eligible dividend from our CCPC, the government is going to look at the tax we paid when the initial income was earned in our corporation. Then they’re essentially going to say, “Ok, we charged you a lot up front, now we’re going to charge you your personal tax rate, and so we’ll refund your corporation some of that tax money, so that the final amount of overall taxation comes close to the goal of tax integration we keep talking about.”

The RDTOH notional account is what accountants and CRA will use to keep track of this tax refundable-money that a corporation can get when it pays out a dividend to you. When big Canadian corporations have paid dividends into your corporate discount brokerage account they will be treated differently than when big corporations from other countries that pay dividends into your corporate discount brokerage account.

Because of this difference, accountants will actually use the ERDOTH and the NERDOTH acronyms to differentiate between the two different types of passive income, and the potential tax refunds each will generate.

Eligible refundable dividend tax on hand (ERDTOH) comes from corporate tax paid on eligible dividends from Canadian corporations and non-eligible refundable dividend tax on hand (NERDTOH) comes from corporate tax paid on other types of investment income.

When your CCPC issues non-eligible dividends to you, it’s going to trigger a tax refund that is being tracked in that NERDTOH account. If you’re planning to amass a large investment portfolio within your CCPC, then you really need to understand how paying yourself a non-eligible or eligible dividend will trigger these tax refunds to your corporation each year.

If you ignore this accounting, you’re going to have a really large tax drag on the dividends you receive in your corporate discount brokerage account. That tax drag gets really notable when you’re receiving dividends from companies outside of Canada, as well as when we’re talking about interest income.

Because of this complicated paperwork and potential tax drag, I think the use of swap-based ETFs makes a lot of sense for folks investing within their corporation. That’s because the ETFs (which I used in the example above) only produce capital gains – no dividends to worry about. And since capital gains are not taxable until they are triggered by selling an investment or “realized”, there can be significant tax deferral.

Remember, that tax deferral not only lets investments compound for longer without the tax man coming in to take his fair share – it also lets the business owner realize the income on their annual taxes whenever it is most advantageous for them (usually in retirement or during a “down year” where their income will be in lower tax brackets).

General Rate Income Pool (GRIP) Account

Many Canadian small business owners will never have to worry about the GRIP account. That’s because it is only for business profit that has been taxed at the general corporate rate. Most CCPC owners will not make more than $500,000 in profits per year, or have $50,000-$125,000 in passive income in a given year to reduce their small business deduction. Because of that, they will never be forced to pay the general corporate tax rate, as all of their corporate earnings will be taxed at the lower small business tax rate.

But for those folks that are fortunate enough to enjoy a large corporate profit in their CCPC and/or build up a sizable investment portfolio within their corporation, they will need yet another notional account to keep track of things.

Again, this is due to tax integration. CCPC owners that pay the higher general corporate tax rate will have a different calculation to make when they pull that money out of the corporation and into their personal spending accounts.

So, the GRIP is going to keep track of the money that you paid the higher corporate tax rate on, because when you pull that money out, it can be in the form of an eligible dividend – as opposed to the non-eligible dividends that most CCPCs pay out (due to the lower small business corporate tax rate they initially paid).

When Should I Take My Investments Out of My Corporation?

Ok, I’m really hoping I didn’t lose you there in all my talk of “make believe” accounts, but as I said upfront, if you really want to optimize investing within a corporation, you have become familiar with the math-heavy details.

I want to quickly reiterate two things:

1) Remember, the whole point of all of this recordkeeping that comes with investing within a Canadian corporation is that you get to control when to take money out of the corporation and pay personal income tax on it.

That ability to control when to take out taxable income can be quite valuable to people who are earning a lot of money in a current year, but believe they will be earning less (and be in lower tax brackets) when they retire, or when they sell the company.

2) It really helps to have someone on your team that knows this stuff inside and out. I’m going to again recommend Objective Financial Partners. They are fee-only financial planners that work with a ton of people who own various types of CCPCs.

I’ve thrown all kinds of questions at them in regards to professional corporations that doctors and dentists have, holding company questions, various capital dividend account (CDA) scenarios, retirement withdrawal monitoring, and much more. They have always been able to look at the big picture from a long-term financial planning perspective, and explain why it would be optimal to pursue a certain path that aligns with my specific goals.

Most of all, OFP will do all that for a transparent fee that is quoted upfront. No commissions or kickbacks, no selling financial products of any kind. You can pay them once, take their plan and implement it yourself (no need to ever pay them again) – or you can set up a recurring meeting where they check in with you once a year, twice a year, or whatever you feel is the right fit. Best of all – there are no automatic annual fees sneakily applied to your account like at most investment advisor firms in Canada. Because they don’t sell anything other than their time.

Ok, so when we look at coming up with a plan for the exact timing of when to take money out of our corporation we’ll want to focus on the following considerations:

- What are our spending needs for this year, and our probable spending needs in future years? By planning our spending we can determine how much money we need to take out each year.

- Are there income-splitting opportunities available for my spouse or children?

- Am I retired or not? This is a very important factor that we’ll discuss in-depth below.

- Do I have a sizable investment portfolio inside my corporation that is generating a substantial amount of passive income each year? If I do, I may want to pay dividends sooner rather than later in order to release the refundable tax (RDOTH) money back into the corporation.

- Should I be contributing to an RRSP, TFSA, RESP, or other personal account, as opposed to building money up in my corporation?

- Where does all of that leave our taxable income number when it comes to federal and provincial tax brackets? If you and your spouse can each take out another $10,000 before you begin to get taxed at a higher rate, you may want to consider that option. The idea being to get as much money on the other side of the “corporate fence” as possible, up to the maximum of a given tax bracket.

What Happens to My Corporation After I Retire?

If you’ve decided to build up an investment portfolio within your corporation, and are now considering retirement, you likely want to know how it will work going forward when you want to withdraw investments from your corporation in order to pay for retirement.

In this context, withdrawing investments from your corporation will be but one puzzle piece to consider in the context of your entire retirement paycheque puzzle. You will have to think about it alongside RRSP withdrawals, TFSA management, CPP & OAS timing, and maybe even a few other uniquely personal income options like downsizing your residence.

It can all add up to be quite a complicated headache. One keep-it-simple strategy I really like for folks with a moderate amount of investments within their corporation (say $500,000 or so) is to sell your corporate investments sooner rather than later, and then use them to pay for retirement when you’re 65- to 70-years old. This way you can defer your CPP and OAS, plus shed the annual fees that come with doing the paperwork for your CCPC.

If you have a ton of money in your corporation, and you may not need it to fund your retirement, you might focus more on post-death considerations. After all, corporations don’t have required withdrawals like RRSPs do (RRIF conversion by the end of the year you turn 71). If you have a lot of money in your corporation you won’t need during your own life, this opens up estate strategies for your beneficiaries.

When you retire, you are no longer going to be running your company anymore, and your corporation will no longer have an operating income. That doesn’t mean however that you must liquidate your CCPC and “cash out” all of the investments in your corporate brokerage account.

You can keep the corporation going and keep filing annual taxes. The main difference is that post-retirement, you will likely opt to pay yourself exclusively through dividends because a salary doesn’t make sense anymore, as you can no longer deduct your salary cost to the corporation if there is no operating profit.

For most retirees, this means planning to pay themselves dividends from the selling of investments (as well as the associated passive income) in their corporate account . If you have been fortunate enough to accumulate large deferred capital gains, selling investments might allow you to pay out tax-free capital dividends. The tax-free portion of a corporate capital gain can be paid out tax-free.

How Will Corporate Dividends Affect My OAS?

One area in particular that you must pay attention to when you withdraw money for your corporation to pay for retirement is how it affects your taxable income – and consequently how it affects your Old Age Security clawback.

As we discussed above, most CCPC owners will be paying themselves primarily with non-eligible dividends. In the first article in this series on CCPC taxes for small business owners we looked at how corporate taxes interacted with our personal taxes.

The non-eligible dividend gross up will be an important consideration for retirees who keep their CCPCs and are withdrawing from them to fund retirement.

If we revisit Olga the Owner (our hypothetical CCPC owner from past articles) and take a look at how withdrawing non-eligible dividends from her CCPC will affect her OAS, we’d have to look at the following math:

- Olga withdraws $100,000 to pay for retirement.

- Olga is retired, and the business has no more operating income, so Olga pays herself $100,000 using non-eligible dividends.

- That $100,000 is grossed up by 15% – meaning that the government is going to “pretend” that Olga’s taxable income is $115,000.

- Sure, Olga is also going to get a tax credit back that is going to recover most of that extra tax – BUT that isn’t going to take into consideration the OAS clawback Olga will get hit with.

- For the full details on the OAS clawback see our OAS guide, but for now just understand in 2024 taxable income over $90,997 is going to result in the government giving retirees less OAS money.

- Olga’s new taxable income of $115,000 after the non-eligible tax gross up is going to result in an “extra OAS clawback tax” being applied to $24,003 ($115,000 – $90,997 = $24,003). That 15% OAS clawback will be equivalent to $3,600.45 in additional taxes for Olga.

Hey, Olga the Owner is still in pretty good shape here. The OAS clawback tax does get exacerbated by the dividend gross up, but it’s not the end of the world. It’s certainly something to be aware of when juggling passive income within a corporation, but I wouldn’t let it be the main consideration.

It does however strengthen the case for my keep-it-simple solution of using the investments within the corporation to pay for life as we defer our OAS and CPP.

What Happens to My Investments In My Corporation When I Die?

When you die, your corporation will be deemed to be disposed of at “fair market value”. It is as if you sold your shares of the corporation and since most people have a nominal cost base for the shares of the corporation when they set it up – like $10 or $100 – basically the whole value of the corporation will be considered a capital gain.

The corporation itself lives on, and the investments within it will have their own tax consequences if and when the corporation sells them, depending on what your beneficiaries do with the corporation.

Your estate could pay a relatively high tax bill, as those capital gains are sometimes quite large – thus generating a tax bill where much of the capital is taxed in the highest tax bracket.

If you knew the day you were going to pass away, obviously you could create a plan to get the investments held within the corporation out in a very tax-efficient way. But of course, very few of us have this “tax-planning luxury.”

So instead we have to balance out the possibility of our estate getting hit with a large capital gains tax bill, with the possible future need for income we will have if we live to be 95+.

If you’ve done the math on your future spending needs and are sure that you won’t need to withdraw money from your corporation in order to fund future spending needs you could look at freezing the value of the shares of your corporation (known as an estate freeze), and then issue new growth shares to your children, grandchildren, or a family trust.

Another strategy involves using money within your corporation to purchase a life insurance policy. I’m not a big fan of this strategy simply because the vast majority of life insurance products that are sold are sold because they make the seller a LOT of money – NOT because they are a good idea for the buyer.

It’s certainly possible that using your corporation to buy the right life insurance policy will be a good idea, and that it will allow you to avoid some tax when you pass along the wealth held inside of your corporation to your heirs. The right policy is probably a policy for someone who has more money in their corporation than they are going to spend during their lifetime. But this is probably a discussion for another day.

BUT – it’s also quite possible that you will be sold a life insurance policy that you don’t really understand just because it generates a big commission for the person doing the selling. If you have reached the level of wealth where you have a large amount of money invested within your corporation, there are other ways to accomplish what these “magical life insurance policies” purport to do.

If you’re at this level of wealth, I cannot recommend strongly enough that you employ a fee-only financial planner that can objectively decide if a life insurance plan designed to pass money down to your estate makes sense is the best route. Don’t rely on a commission-based salesperson to give you a factual analysis of your personal situation!

New Capital Gains Rules for Canadian Corporations

You can read my full article on the new capital gains changes here.

Here are my brief takeaways at the moment:

- The Trudeau government took direct aim at CCPC owners who invest within their corporation (as well as other corporations, including publicly traded companies, earning capital gains).

- Two-thirds of a capital gain earned by a corporation will now be taxed instead of just one-half.

- The new tax rules reduce the incentive to invest within a corporation – thus making it more attractive to pay yourself a salary and generate as much RRSP room as possible.

- There is a chance that a new government could reduce the capital gains tax inclusion rate in the future – so it might be worth it to “ride out” the next couple years and not realize any capital gains in the hopes you can eventually cash them out at a lower rate. On the other hand, it’s possible that if this government is reelected the capital gains inclusion rules could be raised again – or that a new government might leave the new rules in place.

- I used Horizons total return ETFs in my example above, the new capital gains rules mean that those products will now be more valuable to personal non-registered accounts than they will be in corporate accounts. This is especially true when it comes to HXT, as Canadian equities that pay dividends into your corporate brokerage account could have an advantage over capital gains if managed properly.

- There is still a lot of value when it comes to the overall strategy of using your corporation to defer taxes – IF – you’re already in a very high tax bracket at the moment, and will likely be in a much lower one in the future.

Investing Within My CCPC – FAQ

So Should I Start Investing Inside My Corporation or Not?

First off – if you’ve made it through this 3-part mini-series on CCPCs and how to think about taxation when you’re balancing both personal and corporation accounts – kudos to you!

That’s some intense stuff.

The answer to if you should start investing inside of your corporation – or just focus on getting your profits out of the corporation each year, and investing in your personal accounts – can be a very difficult conclusion to arrive at.

It’s difficult to give a one-size-fits-all answer because there are just so many variables. For example:

- How much operating income (profit) is your company going to make this year? How about in the future?

- How much passive income is your company going to make this year? How about in the future?

- What types of investments are you most comfortable with and what type of passive income do they generate?

- How much money do you want to spend this year vs how much money do you want to spend in the future, including in retirement?

- Are there income-splitting opportunities available to your family?

- Do you have a solid accounting team that can help you understand the trade-offs of various types of investments, and accompanying future spending scenarios?

- Are you willing to really get into the nitty-gritty of how to handle the notional accounts when it comes to maximizing your after-tax gains?

Because there are so many variables it’s hard to give any suitable rules of thumb about investing inside a corporation vs outside a corporation.

For me personally, I really think keeping things simple is the way to go. I very much doubt I’ll ever make a corporate profit large enough to worry about investing inside of my corporation(s). Paying myself a salary in order to generate RRSP room, making sure my TFSA is maxed out, and focusing on income splitting opportunities is sufficient for me.

That said, if I was making $300,000+ of profit in my corporation, already maxing out my RRSP, TFSA, RESP, and spousal RRSP opportunities – then I would definitely sit down with my financial advising + accounting team (Objective Financial Partners offers both services) and map out the best mix of salary and dividends over the long run.

I’d also become really familiar with how to best utilize the CDA, RDOTH, and GRIP accounts in order to give myself the best chance at paying less tax in retirement. In a perfect world, a CCPC owner making that much money could invest within their corporation, avoid paying the highest possible income tax rates in Canada when they were at their earnings peak, and then withdraw investments from their corporation once they are retired and in lower brackets.

The key is to accomplish that goal with as little annual tax drag as possible – so fully understanding swap-based ETFs and/or how to use the notional accounts becomes essential.

Hello Kyle!

Great articles on small businesses and how the taxes work.

I have some questions:

a. If you have a small business and are investing within your corporation and get some dividends/capital gains from ETFs/Stocks, if you want to minimize the taxes, Ed Rempel recommends you pay them out to yourself. Do you have to pay them out that same month that you receive them or can you wait till before your business year end, add up everything and then pay it out all at once?

For this pay out, does it go from your self directed investing account to your company account and then to you personal account?

b. What about phantom distributions from ETFs? (sometimes you get them at the end of the year from ETFs.) How do you deal with that in the small business investing account?

c. If the corporation is not earning active income (retired owner) and is left open just for the passive income (investments) does the company type need to be update from say Consulting to Investments?

d. Once the owner retires, how long can the corporation be left open? I understand you would still have to file business taxes and maintain the business registration. Just wondering if there is some sort of deadline to close the business and get your investment money out.

Thank you, RK

Hey Rahim,

I’m going to cop out here and say that there are so many variables involved in these questions that you really need individualized advice. If you tell Objective Financial Partners that I sent you, they’ll probably give you a bit of a deal. Real quick – your questions are excellent – make sure you also check out the article on selling your business that I wrote last week.

Thanks for the feedback Kyle.

Did you ever find out the answers Rahim? Care to share?

Hello Ali K,

I never got answers to my questions but this is the first year for investing with corporation. So far I tallied up dividends received during the business year, sent that back into business chequing account and then wrote a personal cheque for that amount. Waiting for accountant to do business taxes, then I will see how it worked out for year 1.

Thanks, Rahim K