Capital Gains Refund Mechanism – Why Mutual Fund and ETF Investors Potentially Pay Less Tax

When I see tax returns for do-it-yourself investors, I am often struck by how much tax they pay on their investments.

Many high net worth investors also pay a lot of tax on their investments in “Separately Managed Accounts” (SMAs), which are marketed as being tax-efficient. With an SMA, you hire a portfolio manager directly to manage your account. It is like a mutual fund, except that you actually own the underlying stocks and bonds yourself. The marketing line is that you pay less tax because your cost base is your own and not shared with other investors, like it would be in a mutual fund.

However, when I see tax returns for mutual fund investors, most of the time they pay very little tax on their investment income, even when their investments are up a lot. Why? A significant part of the reason is the “Capital Gains Refund Mechanism” (CGRM).

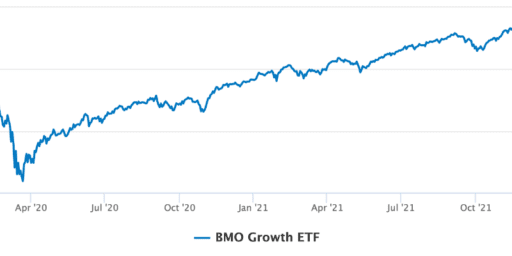

In short, mutual fund investors that continue to hold their fund receive credits from the investors that sold. This means that mutual fund investors can often hold their funds for many years and claim little or no capital gains tax, even when the fund has risen sharply and the fund manager is actively buying and selling stocks within the fund.

The CGRM is a little-known benefit of fund accounting. It is designed to prevent double tax. If the holdings in a fund go up, then the fund also goes up. It would be double tax to tax both the holdings and the fund on the same growth.

An Example

Let’s say there are only 2 investors that invest $100,000 each in a mutual fund, which invests in only 2 stocks. Both stocks double in value. Just before the end of the year, investor B sells his fund, while Investor A continues to hold it. Within the fund, stock B is sold and stock A is not.

What are the tax consequences?

Investor B: Capital gain of $100,000

He invested $100,000 and sold it for $200,000, so he claims a capital gain of $100,000. (Since only half is taxable, this is a taxable capital gain of $50,000.)

Mutual fund: No tax

Mutual funds never pay tax because they pass on any taxable income to the fund investors. However, in this example, there is no taxable income in the fund to pass on. The fund sold stock B during the year, which also had a gain of $100,000. However, the gain is not taxable to the fund. The gain inside the fund is really the same gain that the investors received. To avoid double tax, the mutual fund receives a credit for the gain claimed by investor B. In short, the capital gain within the fund is allocated to investor B who sold.

Investor A: No tax

His fund doubled, but he still owns it, so no gains are triggered. He receives no tax slip from the fund, since the gain within the fund was allocated to investor B who sold.

What if Investor A owned the same stocks directly, instead of the mutual fund? If she invested $100,000 directly into the same 2 stocks ($50,000 in each) in a brokerage account or in a Separately Managed Account and then sold stock B, she would have a capital gain of $50,000. This gain is from stock B doubling and being sold.

In short, with the exact same stocks and transactions, the tax consequences on their tax return are:

- Do-it-yourself investor. Owns stocks in brokerage account: $50,000 capital gain.

- High net worth investor. Owns stocks in Separately Managed Account: $50,000 capital gain.

- Mutual fund investor. Owns mutual fund that owns the stocks: No tax.

For the mutual fund investor, the capital gain is deferred until she sells the fund in the future. The CGRM also applies to ETFs and pooled funds, as long as the management company knows about and calculates it.

How well the CGRM mechanism works depends on the turnover within the fund, the amount of capital gains (less capital losses) within the fund, and how many investors sell at a gain. Fortunately for long term investors, the average holding period for equity mutual funds is 3.29 years, according to Dalbar. This means there should be significant credits from investors that are selling in most years.

If the average investor sells the fund every 3.29 years, then on average the fund could sell all the stocks it owns every 3.29 years with little or no capital gain to pass on to the long term investors in the fund.

Note that investors owning the stocks directly can also defer tax if they hold onto all their stocks, or if they sell losers to offset any winners. The difference is that mutual fund investors can have the fund manager buy and sell stocks when they think it is appropriate, and they may be able to still defer the tax.

In addition to the Capital Gains Refund Mechanism (CGRM), the other main reason that mutual fund investors may generally pay less tax on their investments is because of corporate class mutual funds. That is a topic for another day.

About the Author: Ed Rempel is a Certified Financial Planner (CFP) and Certified Management Accountant (CMA) who built his practice by providing his clients solid, comprehensive financial plans and personal coaching. If you would like to contact Ed, you can leave a comment in this post, or visit his website EdRempel.com. You can read his other articles here.

I've Completed My Million Dollar Journey. Let Me Guide You Through Yours!

Sign up below to get a copy of our free eBook: Can I Retire Yet?

Hi Fiscally Fit (#11).

I agree completely. Tax planning is a predictable gain. It’s the easiest ROR.

Ed

Getting qualified dividends taxed at the 15% rate is definitely the way to go for investing.

Any trader will almost always lose over the long run!

Tax planning, the easiest ROR you will ever make haha. So many people forget this.

I always get a kick out of people who “hate” mutual funds… or index funds…etc. These things are just tools. They are not good or bad, they simply do what they are designed to do and work well in the appropriate situations.

People get so preoccupied with the buzz words of the day, ETF, fees, MER, transaction costs; they actually start to ignore all the other stuff that is just as important. Anybody that “hates” a certain type of investment vehicle but cannot at least identify to me the metric they use to measure “risk” in their own portfolio erodes all credibility.

Thanks for checking on that Ed! Unfortunately the demand for corporate class index funds is probably very low. Fortunately I have other ways of handling rebalancing to minimize taxes such as simply using new contributions to make up the difference or shifting funds in other tax-sheltered accounts. As you suggested, I still need to do an analysis of actual taxes to see which indexes will be best for taxable accounts.

As for your last question, I am both :) I attempt to buy broad indexes (and nothing else) when they are cheap. Since the average investor underperforms both the funds they are invested in and the market indexes, I want to see what happens by doing the opposite of what they do.

Hey Value,

Didn’t finish that last post. We should create an MTER (sounds like nobody in the emergency room) as the total cost MER + tax. Divide the tax you pay on your investment income by your amount invested to get a tax %. Then add that to your MER.

Once you have your total cost MTER, you can evaluate that against the quality of stock picking you are getting for your cost.

I’ve been meaning to ask you, Value, are you a value investor or an index investor?

Ed

Hey Value,

Yes, thank god for the traders!

Corporate class structures usually add little or no extra cost. For most companies, the corporate class version of a fund either has the same MER as the non-corporate class version or is higher by a minor amount, such as .02-.03%.

Whether or not it is worth it depends on how much tax you pay on investment income now. It is useful to add the costs MER + tax. If a fund has

I am not aware of any, so I checked Morningstar and could not find a single index fund available in corporate class.

This is good to know Ed. I’ve noticed that well-managed ETFs, like those provided by Vanguard, always seem to be able to avoid causing extra taxation. Those investors who can’t hold on to one fund for long are doing us a great favor!

I’ve been looking at potentially using some corporate class funds soon, but I’m not sure if the tax savings are worth the extra fees and the potential requirement to use an active manager. Do you know of any corporate class index funds with low fees?

Hi Krantscents,

Yes, I agree. However deferred capital gains are even better.

Ed

Hi FT,

Yes, there could be capital gains distributions. You would have lower taxable capital gains, though, than you would if you owned and sold the same stocks (assuming you continue to hold the fund and anyone else sold the fund during the year).

Some fund managers tend to hold their stocks for many years, while others are very active traders. Morningstar today shows some funds with a 750%/year average turnover and some less than 1%/year. The high turnover would usually create a lot of taxable capital gains, while the low turnover funds would produce hardly any taxable gains.

There are several steps for reducing capital gains tax for any stocks sold within the fund sold at a gain:

1. Net against any stocks in the fund sold at a loss.

2. If a capital class mutual fund, net against net capital losses of any other fund in the capital class structure. (There usually are some, because these structures tend to have a wide variety of funds, including sector-specific and country/region specific.)

3. Use the Capital Gains Refund Mechanism to allocate capital gains to investors that sold the fund.

4. Apply any remaining gains against the costs of the fund. (This roughly means that the taxable 50% of the capital gain is netted against the MER.)

If there is still a taxable capital gain left, it is allocated to the owners of the fund.

Ed

Great tax information shrouding another fine piece of mutual fund propaganda.

Good thing the author doesn’t sell and/or otherwise profit from the sale of mutual funds.