Why I Don’t Invest in Chinese Stocks

Technically, l I guess that I can’t say that I don’t invest in Chinese stocks at all, since I advocate for using Canadian all-in-one ETFs, and have ETFs such as VXC on my best Canadian ETFs list.

That said, I would never advocate for investing directly in Chinese stocks. I didn’t like the idea when their stock market was on a tear – and I definitely don’t like it now when it’s struggling! It should go without saying that you won’t find any Chinese stocks on my best dividend stocks list either, because most Chinese companies don’t pay dividends.

Due to some of the more positive headlines about Chinese stimulus these days, I’m seeing more and more columns being written about companies listed on the Shanghai and Hong Kong stock markets. Perhaps it has something to do with the rich valuations that US tech heavyweights are currently trading at.

In any case, I can see the allure of the high growth rates and the sheer scale of the domestic economy in China. That said, there are just so many risks and tradeoffs that we aren’t familiar with in the Western market when it comes to investing in Chinese equities.

Regulatory Uncertainty in the Chinese Stock Market

The Chinese government’s regulatory framework is a moving target. The constantly changing rules create a volatile and unpredictable environment for investors. Regulatory crackdowns, often sudden and far-reaching, have hit industries like technology, education, and real estate, wiping billions off the valuations of once high-flying companies.

For example, in 2021, the Chinese government essentially banned online for-profit tutoring companies, devastating a multi-billion dollar sector overnight. (And putting thousands of native-English-speaking digital nomads out of work.) Similarly, tech giants like Alibaba and Tencent faced fines and restrictions as part of a broader antitrust crackdown.

Google “Jack Ma” (often referred to as the Chinese Jeff Bezos) for more details on how visionary entrepreneurs can sometimes be treated in China. These decisions, often lacking transparency or clear communication, leave investors exposed to risks that are virtually impossible to predict.

For investors, this means the fundamentals of a Chinese company may no longer matter as much as the whims of policymakers. The Chinese government maintains varying degrees of control over most large Chinese companies. State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) dominate sectors such as energy, banking, and telecommunications, while even private companies are not immune to government interference.

That heavy government involvement in the stock market can significantly erode shareholder value. For example, the rise of “golden shares” allows the government to secure controlling stakes in private companies, ensuring alignment with the government’s political objectives – as opposed to simply maximizing shareholder value.

Accounting Transparency Issues in Chinese Firms

I personally think that the most underreported concern in regards to investing in Chinese companies is the lack of accounting transparency. Reliable financial reporting is the unsung hero of functioning investment markets.

Without confidence that investors can rely on the data companies are showing them, it’s impossible to believe they can determine the fair value of a company. The absence of consistent oversight in Chinese firms leaves investors vulnerable to manipulation and outright fraud.

This issue is compounded by the use of complex corporate structures, weak enforcement of international accounting standards, and limited auditing access for foreign regulators. Chinese companies usually operate under different reporting standards than those enforced in North America or Europe. While many publicly-listed companies claim to use International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), the actual enforcement of these standards is inconsistent.

This lack of oversight creates an environment where you can’t really trust the numbers that companies are putting forward.

And I get it if you read that and thought, “Well, aren’t there a few companies in the rest of the world doing this?” Fair point – but usually those companies are caught and punished (by shareholders if not governments) sooner rather than later. There’s also a question of frequency and scale when it comes to “creative accounting”.

One prominent example of the problems that commonly occur is Luckin Coffee. This caffeine darling was once hailed as the “Starbucks of China”. The company went public in 2019 and caught investors’ attention based on massive revenue growth and excellent prospects within the Chinese market. (Any time you can be the “Starbucks” of anything, AND any time you can be the “of China” for anything – that intuitively sounds like a good sales pitch.)

However one year later it was revealed that Luckin had made up over $300 million in sales by creating fake transactions. The stock plummeted by 75% in a single day, was kicked off of stock exchanges, and crippled many investors.

For a more recent example, just look at the currently-unfolding Evergrande scandal. China Evergrande Group, one of the country’s largest real estate developers, reported strong revenue and asset growth for years – while brushing their massive debt under the table.

How was it able to do all that brushing one might ask?

With the help of blind eyes from multiple layers of government. The local Chinese governments had every incentive to keep these land development deals going no matter what. I think we have yet to uncover just how many liabilities the company has that were never officially on its balance sheet. While the Chinese government stepped in to help out domestic bond holders, shareholders and foreign bond holders were basically wiped out.

Geopolitics and Chinese Investments

China’s strained relationships with Western countries – especially the world’s largest economy (by far) United States – adds another layer of complexity to consider when trying to consider the value of any single Chinese company. Every company in the world has these types of considerations (just ask the folks who were banking on the Keystone XL pipeline). But large Chinese companies appear to be running up against geopolitical constraints more than most – and they’re constantly evolving.

Just look at Canada’s relationship with China as a non-US example. A few years ago, Huawei was a good bet to land billions of dollars worth of business across Canada. (Ironically, it may have benefited from stealing Canadian technology in order to get a competitive advantage.) That momentum then turned on a dime when the Canadian government essentially banned the company. There were fallout shocks across both economies from that decision.

More recently, in order to make sure they were appropriately positioned for all-important free-trade talks with the USA, Canada bowed to US pressure and put a 100% tariff on Chinese EVs – effectively banning them. Oh and then there’s the whole Tik Tok saga (perhaps best explained here by John Oliver).

That’s all before we mention the massive elephant in the world of some sort of conflict over Taiwan – perhaps the largest geopolitical concern on the planet!

China’s Economic Slowdown

While China’s economy has grown rapidly over the past few decades, recent data points to a slowdown. Structural issues such as rising debt levels, demographic challenges, and decreasing productivity have raised concerns about long-term sustainability.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that a rapidly-greying population isn’t a recipe for economic growth. Less consumers, more pensioners isn’t great math for China. Unlike Canada and even the USA to a large extent, China isn’t used to integrating large numbers of immigrants in order to moderate the aging trend. Large groups of immigrants aren’t exactly climbing over themselves to move to China, work for relatively low wages, and have to learn Mandarin or Cantonese.

Add to those aging population struggles, the challenges of growing debt hangovers, trade-wars, increased military spending – and the whole thing can look pretty shaky. You toss in the impact of a warming planet, and a possible military confrontation in the South China Sea, and the probabilities that Chinese stocks are a bad long-term investment start to build up.

Finally, when it comes to their currency, the Chinese Yuan is tightly controlled by the government, making currency risk another critical factor. Fluctuations in the yuan’s value, driven by political or economic pressures, can significantly impact the returns on Chinese investments. For example, during periods of trade tension, the Chinese government has allowed the yuan to depreciate to make exports more competitive. While this benefits exporters, it can erode the value of foreign investors’ holdings.

Chinese ETF Exposure

Despite all the economic headwinds that I just listed above, I actually think the Chinese economy will grow in the next few decades (just not nearly as quickly as they claim it will). The bigger issue for investors is whether any of those gains will translate into increased profits for Chinese companies.

After all, many companies sell products in China, and benefit from their increased economic might. If you’re invested in Apple, Tesla, or Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy (LVMH), then you already have exposure to the Chinese economy.

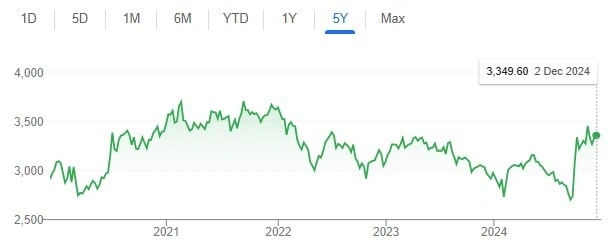

Chinese economic growth for the last five years has been 5% – pretty solid compared to much of the rest of the world. Yet here’s what the Shanghai Composite Index (where many of China’s largest stocks are listed) has looked like.

SSE Composite Index:

Pretty lackluster growth.

That said, if you’re invested in an ex-Canada ETF (such as VXC) or an all-in-one ETF (like VEQT or XEQT), then you actually already have some direct exposure to Chinese stocks.

| Country | Percentage (%) |

| United States | 46.43 |

| Canada | 24.83 |

| Japan | 5.48 |

| United Kingdom | 3.33 |

| Switzerland | 2.11 |

| Australia | 1.91 |

| Germany | 1.83 |

| China | 1.31 |

| Netherlands | 1.02 |

| India | 1.01 |

VEQT:

| Country | Percentage (%) |

| United States | 45.77 |

| Canada | 30.22 |

| Japan | 4.07 |

| United Kingdom | 2.51 |

| China | 2.05 |

| India | 1.61 |

| France | 1.57 |

| Switzerland | 1.45 |

| Taiwan | 1.42 |

| Germany | 1.34 |

| Australia | 1.30 |

| Republic of Korea | 0.79 |

| Netherlands | 0.64 |

| Sweden | 0.57 |

| Denmark | 0.49 |

VCN:

| Country | Percentage (%) |

| United States | 65.24 |

| Japan | 5.91 |

| United Kingdom | 3.65 |

| China | 2.92 |

| India | 2.30 |

| France | 2.29 |

| Switzerland | 2.11 |

| Taiwan | 2.02 |

| Germany | 1.94 |

| Australia | 1.89 |

| Republic of Korea | 1.15 |

| Netherlands | 0.92 |

| Sweden | 0.83 |

| Denmark | 0.71 |

| Italy | 0.70 |

The competition between the best online brokers in Canada, has led to Qtrade offering free ETF buying and selling of XEQT, as well as its less risky all-in-one cousins, XBAL and XGRO. There’s also a China Index ETF available: XCH (but as you’ve likely gathered from this article, I’m not a fan). You can see our full Qtrade review for more details.

One Chinese Stock I Might Consider

Other than the Dogs of the TSX moves that I make, I’m not a big stock picker these days.

That said, as an engineer, there is one company that has caught my attention over the years.

Really, it’s the whole Chinese Electric Vehicle (EV) industry in general – but it appears that Build Your Dreams (BYD) is shaping up to be the unstoppable force that will outcompete the rest of China’s automakers.

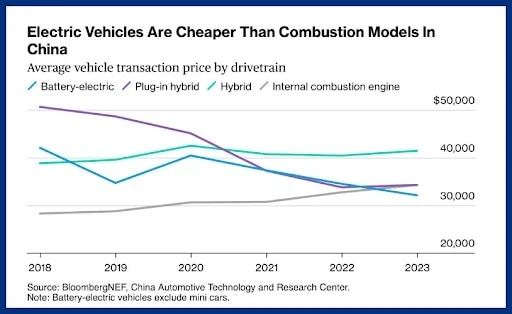

The growth of the company has been incredible, and the cut-throat competitions between Chinese EV companies has led to plunging costs. It has now gotten to the point where EVs are cheaper than traditional internal combustion (ICE) engines. I’m not talking about “lifetime ownership costs” – I’m talking straight up, price tag on the car lot costs.

If you want to know how the EV end game is likely to play out, take a look at Australia (who offers an equal playing field, with no tariffs on any vehicle imports). Chinese EVs now make up 80% of the EV market there!

The fact that Warren Buffett owns a solid chunk of BYD further piques my interest. As I said above, I’m not a big fan of Chinese stocks, but if I had to pick one, BYD would be the bet.

Great article on investing in China if anyone wishes to know risks and rewards. I feel that way, high risks and unpredictable rewards. May be kind of casino scenerio. Definitely not suitable for longterm steady investors with clear goals.

I have long given up on Chinese stocks.

The lengths some companies have gone to conceal misdeeds.

If you read some of the reports published by short sellers, the reports are eye opening.

There is the problem of not adhering to common accounting standards and the arrest of people who go out and confirm facts on the ground in China.

Till they evolve to a higher standard and really open the books to all, investing is a gamble.

I almost forgot the war on keeping business people towing the countries political lines is problematic. The rule of law is necessary for investors knowing that fairness in treatment is present.